Lugas Raka Adrianto

It is inevitable to predict society without growth in the next 2050. UNEP global resources outlook report in 2019 has outlined that our resource use and demand bolster global-wide economic development, but much is at stake1. The environmental costs, associated with production of metals without future considerations, have aggravated the natural balance if the way we do things remain the same. The conundrum is: how do we manufacture materials sustainably? Presuming we are already in this direction, are we doing it good enough?

Progressing without compromise: can we?

The circular economy concept has long been wandering around media and scientific community. The consensus is clear – transitioning into this system is a necessity to maintain an ever-increasing material demand. Yet, when we consider its real application in a resource-intensive industry like mining sector, particularly far in the upstream, the idea seems to be unanswered. As our needs to produce diverse metals grow larger, naturally the disposal of waste follow the same trend. This does not sound promising if we advocate for UN SDG No 7 on providing clean and affordable energy for all by 2030, while ignoring the fact that our energy transition requires plenty of metals as the building blocks2.

How do we overcome this dilemma? Where should we start fixing materials production?

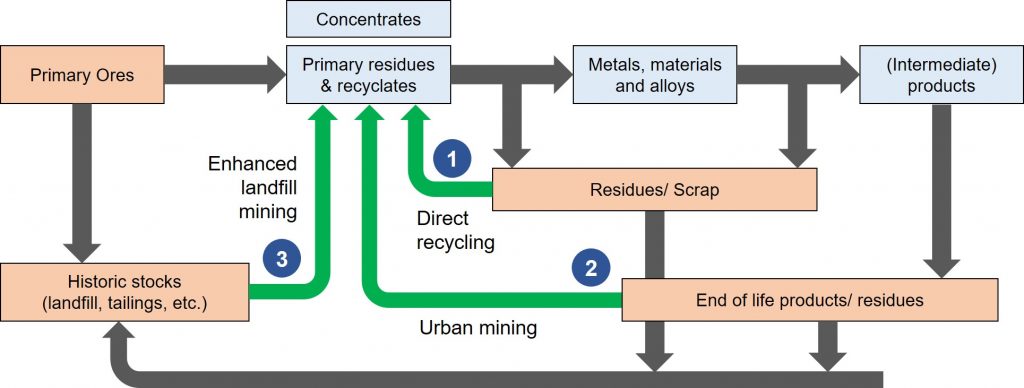

Some researchers are trying to identify the losses of material in the value chains in order to detect inefficiencies. According to recent findings3,4, most of our operational production systems can minimize leaks of valuable metals, mainly by concentrating on three flows (see Figure 1).

Figure 31.1 – Ways to close the loops in circular economy. Reproduced from Jones et al. (2013)

One study found that flow Nr. 3 (enhanced landfill mining) is becoming point of interests, simply because we have been neglecting these historic stocks while it continuously accumulates resources (i.e. metals). For instance, in the case of Nickel, on average up to 20% of this flow ‘escapes’ and remains dormant when no recovery systems are in place.

What to do with these abandoned dumps?

The benefits of reprocessing and recovering valuable metals from these sources are twofold. Firstly, we should always prioritize safe decommissioning of today’s disposal; in other words, storing these wastes with the least amount of health and environmental risks5. Retreating historic stocks not only means that we only focus on the metals of interest, but also on the overall ecological processes. Accelerating this new pathway will unlock new scenarios where abandoned waste stocks can be innovatively transformed from aforementioned environmental burdens into resources; an alternative solution that can contribute to sustainable development.

Back to reality: Have we begun? What should we expect soon?

In some cases, tailings may have significant amount of metal content from past productions. These facts, combined with key refinement technologies6 and market demands, might push mineral companies to reassess their old assets. An example is gold recovery from traditional tailings in South Africa where they discover plenty of gold left in the waste form7. In parallel, the situation calls for better valuation of resource availabilities; efforts should then be pushed towards acquiring metals from ‘low-hanging’ fruits rather than letting metals leak out in the conventional system4. However we look at it, the strategy described above would not resolve all resource demand problems at once. Nevertheless, it is a great step, and only until we couple transitions together (i.e. energy, resources, and others), then we can aim for future trajectories with much larger environmental benefits.

References:

- UNEP. Global Resources Outlook 2019: Natural Resources for the Future We Want. (2019).

- World Bank Group. The Growing Role of Minerals and Metals for a Low Carbon Future. (2017).

- Jones, P. T. et al. Enhanced Landfill Mining in view of multiple resource recovery: a critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 55, 45–55 (2013).

- Reck, B. K. & Graedel, T. E. Challenges in Metal Recycling. Science 337, 690–695 (2012).

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. From risk to resource: waste can contribute to sustainable development. https://www.unece.org/info/media/news/sustainable-energy/2017/from-risk-to-resource-waste-can-contribute-to-sustainable-development/doc.html (2017).

- Reuter, M. A., van Schaik, A., Gutzmer, J., Bartie, N. & Abadías-Llamas, A. Challenges of the Circular Economy: A Material, Metallurgical, and Product Design Perspective. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 49, 253–274 (2019).

- Deloitte. Converting Tailings Dumps into Mineral Resources. https://www2.deloitte.com/za/en/pages/energy-and-resources/articles/converting-tailings-dumps-into-mineral-resources.html (2015).

Media Attributions

- Closing the Loop in CE