Queenie Lu

According to Blöbaum (2016) trust is no longer a relation factor between individuals but rather a crucial factor for companies, institutions as well as social systems, such as politics, health care, the economy, media, and science. But along with its technological advances, digitalization brings a new challenge for the relationship between trustor and trustee. This article will focus on how trust has changed over time and what is needed from leadership to guarantee cybersecurity.

The Impact of Digitalization on Society

Digitalization is currently contributing and will further contribute to the different aspects of sustainability. In the ecological field, it will bring improvement in forecasts of natural events, global food production, management of greenhouse emission, etc. From an economic point of view, the digital transformation will yield an overall efficiency in the consumption of e.g. resources, energy, and time. But even more important is the effect of digitalization on the social aspect of sustainability. A key component for concepts of social sustainability is “the ability and willingness of a society to develop processes and structures that not only meet the needs of its current members but also support the ability of future generations to maintain a healthy community and intergenerational justice” (Osburg, 2017, S. 6). This willingness is thus a decisive factor for the long-term future wellbeing of our planet. It involves a lot of trust in institutions and companies as well as ethical behavior of organizations, which will be challenged by digital transformation. Digitalization will deliver new society models. For example, there will be new economic models, where personal data is exchanged for free services or products. Ethical projects can be facilitated through crowdfunding, mobility is going to enhance availability and connectivity and so on. There are three major areas of digitalization that have an impact on our society, namely Data, Algorithms, and Bots (Osburg, 2017).

Having access to customer data is a competitive advantage, which allows more precise customer targeting, better-suited prices, offers and ads. Tracking tools are no longer a phenomenon within the online world. In-store systems, like face-recognition softwares, are getting more and more common. Staying anonymous and not revealing our data is almost impossible. The majority of costumer are aware of this fact. But to most of us, it stays intangible what kind of data and at what cost this data is given away. This is where trust comes in. Customers need to provide unintentional trust to the data-owner that their data is used confidentially (Osburg, 2017).

In the beginning, the Internet was dominated by openly available information for all, the so-called freedom of internet. However, non-transparent algorithms have taken control over information distribution. They reduce the breadth of information that the user is exposed to down to what the user might like, acting as a self-reinforcing force. This has tremendous implications for any kind of public discussion, especially political discussion (Osburg, 2017).

Lastly, digitalization will significantly change the job market. It is still widely speculated whether the emergence of new jobs through technology could cover the loss of jobs. It is estimated that 10-20 % of all current jobs might disappear, whereas another 20-30% are highly affected by digitalization. Even though shifts in job markets are nothing new, the change that digitalization brings is alarming since machines carry out increasingly more intellectually challenging tasks. So there are a lot of uncertainties in which jobs will be replaced by bots (Osburg, 2017).

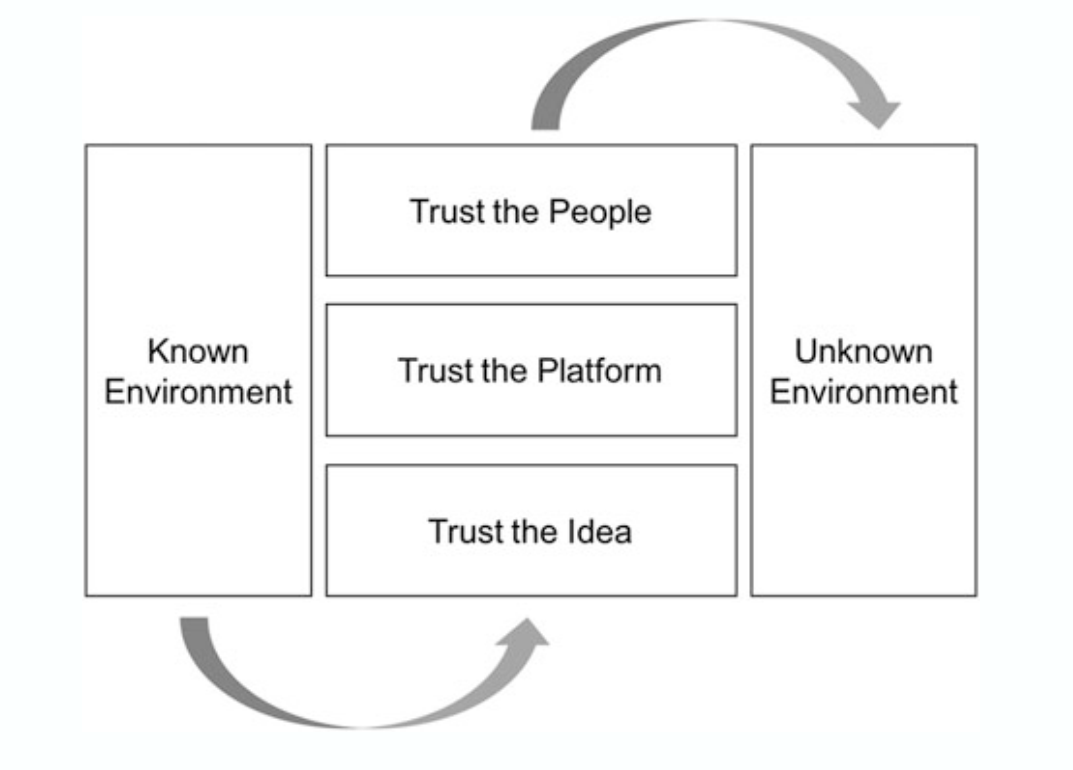

Change in Risk Perception and Trust

From a historical point of view, there are three different types of risk concepts depending on the progress of human society. Before modern times, dangers were seen as an inevitable part of human existence. These dangers consist of natural phenomena, such as hunger, floods, and illness. Religion gave humans an explanation for these incidents. The human wasn’t responsible for these. This changed around the sixteenth century with the discovery voyages and uncertainty of safe return. People started to realize that, different from what some religions say, you could take your own destiny in your hands. The modern risk as we know it today emerged during industrialization. Dangers are no longer of natural origin but are rather human-made, manufactured. It makes a difference whether an earthquake is caused by tectonic plates or by shale gas explosion. Danger has become a part of science, technology, and industry. A whole system of institutions and regulations were developed that accompanied the emergence of manufactured risks. Risks for individuals were researched, calculated and more importantly prevented if possible otherwise compensated. This system provided sufficient assurance to the general public until the mid-twentieth century. Humans increasingly became aware of these risks through major accidents or sudden discoveries such as the accident in Chernobyl or the NSA spying on people which exposed to many the risks of the digital age. But even more shocking is the fact that the system is unable to prevent in an absolutist certain way which leads to doubts. Even though technology can bring a lot of advantages, does it outweigh the potential risks, does it outweigh the doubts that people are having? Especially since all the advantages that digitalization should bring to our society are currently still promises. People have no other choice than to simply trust. But this trust is markedly strained. Generally, citizens are concerned about the lack of privacy and intransparency of their data. As mentioned above, it is unclear what data is given. But more importantly, it is obscure who is using the data, for what it is used and what value it has. Who controls the algorithms? What jobs are at risk? These are all questions that can’t be answered yet. This uncertainty and lack of knowledge create distrust. Interestingly, findings suggest that the Informed Public, university graduates who follow the media and have incomes in the top 25%, is more trusting towards institutions than the general population is. The latter one probably tends to under- or overestimate risks. Anyhow, this proposes the idea that people who understand and are adaptable to these changes are more likely to trust. But the education level is not the only factor influencing trust, social media has its fair share as well. The general public consumes information less through newspapers and more online. Self-affirming online communities are seen as the most credible source of information. Another unsettling results come from a survey. The results show that innovation is seen being motivated by technology, business target and greed and less by the ambition to improve people’s lives. Overall, a shift in trust is noticeable, from trusting institutions to trusting individuals. There are new economic models emerging, making use of this new model of trust, namely the sharing economy. It is based on the peer-to-peer marketplace. However, there is a concept called Trust Stack that is very helpful for understanding how trust can be improved at three different levels. As you can see in the figure below, people being in a familiar environment has to go through three stages before they dive into an unknown environment. Firstly, they have to trust that the new idea is safe and worth trying. The second stage is trusting the platform, system or company. Lastly, they need to trust other users while interacting with each other (Osburg, 2017; Schepers, 2017).

Figure 99.1 – Fig. 1: Trust Stack

The Need of Change in Leadership

Despite how great the advantages of digitalization are, if people do not want it, regardless for rational or irrational reasons, there will be an uprising of resistance in the commercial and political systems. They will be most likely justified for ethical reasons, protection of civic rights, human rights or social protection systems. The acceptance of manufactured risks depends strongly on the society, its culture and ethical viewpoints. Thus, a simply better or more communication with the general public will not be as big an use as one’s first impulse would say. It is difficult to regain the trust of society, when there is the belief that these risks are not constructed by laypeople but by experts themselves. Especially the internet on a global scale causes new challenges for political and company leaders. The internet needs to be secure so that the protection of individual liberties, the right of informational self-determination of citizens and of democracy can be guaranteed. The internet has no geographical or state-related border which makes it peculiarly difficult to secure. Every nation has different geostrategic positions, national economic policies, successful technical innovations and security policies. Citizens have different views on privacy and personal rights. For example in Germany, the government is required to secure its citizens’ rights to data protection, which is rooted in basic law. Consequently, the main goal of the EU, with Germany as a major stakeholder, regarding cyber policy is to strengthen systematic resilience and to be able to recover from attacks and fraud. Whereas the US citizens do not see it as the government’s responsibility to secure their personal rights. Thus, this demands a close cross-border collaboration involving national as well as international regulatory processes. Cybersecurity policy would need to be formulated and implemented on a global multi-level and multi-stakeholder structure. Additionally, technical measures are needed. Physical infrastructure like encryption technologies, that allow only authorized parties to read information, could protect today’s digital society. However, on the first line of defense, every state is required to do everything possible to prevent actions originating in its own territory (Feldner, 2017).

But how can we regain the trust of people in this time of change? The problem is that we promise stability after all this change. There might be a time where there is no change, but this will last most likely for only a short time. In that way, we create expectations about stability and change, the latter being perceived as something negative, as an unsafe environment by society. Thus, it is essential to advocate change, take the fear of change off people. It is important that leaders promote learning instead of stability. It is necessary that it is clear to the general public that success only comes with trial and error. This last point sure does sound more easy than it is. Changing the opinion of people is one of the hardest thing to do. But in essence, I believe that this is the best long-term solution for increasing the acceptance of digitalization(Feldner, 2017; Matser, 2017).

References

Blöbaum, B. (2016). Key Factors in the Process of Trust. On the Analysis of Trust under Digital Conditions. In B. Blöbaum (Ed.), Trust and Communication in a Digitized World: Models and Concepts of Trust Research (Issue February, pp. 3–25). Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28059-2

Feldner, D. (2017). Sovereign Decisions as a Means for Strengthening Our Resilience in a Digitalized World. In T. Osburg & C. Lohrmann (Eds.), Sustainability in a Digital World: New Opportunities Through New Technologies (pp. 59–75). Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54603-2

Matser, I. (2017). Leading Change in Ongoing Technological Developments: An Essay. In T. Osburg & C. Lohrmann (Eds.), Sustainability in a Digital World: New Opportunities Through New Technologies (pp. 95–102). Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54603-2

Osburg, T. (2017). Sustainability in a Digital World Needs Trust. In T. Osburg & C. Lohrmann (Eds.), Sustainability in a Digital World: New Opportunities Through New Technologies (pp. 2–20). Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54603-2

Schepers, S. (2017). The Risk Averse Society: A Risk for Innovation? In T. Osburg & C. Lohrmann (Eds.), Sustainability in a Digital World: New Opportunities Through New Technologies (pp. 21–36). Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54603-2

Media Attributions

- Bildschirmfoto 2020-05-25 um 21.18.40