Canxi Chen

Climate change and related natural disasters have negative impacts on human health including mental distress. The vulnerability to associated mental burden varies across communities and individuals, and healthcare service should get prepared, especially for people with high risk. Eco-anxiety as an adaptive response may motivate favorable social mobilization and activism.

The world that humans live in has evolved dramatically over the past few hundred years. We might expect ourselves and our society to be well-prepared to confront the changes happening in the living space, equipped with sophisticated civilization and technologies. It is true to some extent. Due to the global pandemic and the new experience of regional lockdown, many have reflected on how heavily our well-being relies on the daily routines, and on whether we can adapt when life activities are constrained and threats come close.Unlike infectious diseases and many non-communicable diseases (e.g. respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease), the impact of climate change on mental health received comparatively less attention. Climate-change-related mental health burdens should be more addressed in health impact discussion and we need to tackle the anxiety with good interventions and planning.

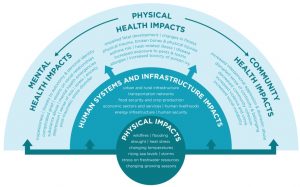

Figure 30.1 – Source: Clayton, S., Manning, C., & Hodge, C. (2014). Beyond storms & droughts: The psychological impacts of climate change.

Impact of weather- and climate-related natural disasters on mental health

Changes in meteorological factors, seasonality, and exposure to natural disasters, will directly influence psychological health and well-being. As one of the most threat to humanity, climate change is likely to increase the frequency, extent, or intensity of extreme weather events such as heat waves, wildfire, droughts and flooding. Exposure to these events can result in a mental health burden, which is largely hidden, such as anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder1. Extreme heat, in particular, increases both physical and mental health problems in people with mental illness, raising the risk of disease and death. It is because many psychoactive prescription medications impair the body’s ability to regulate temperature1. Such natural events also could interrupt the institutional function to provide mental health and well-being services. Researchers have found that a significant proportion of people affected by climate- and weather-related natural disasters develop chronic psychological dysfunction.Indirect impacts of negative environmental conditions will gradually evolve and result in cumulative environmental stresses on livelihoods, economic opportunity and social conditions2. Climate change would consequently change people’s place attachment, disrupt cultural continuity, impair food and nutrition security, force human mobility, and lead to intangible loss and damages. It would bring a negative impact on mental well-being, including feelings of anxiety, grief and loss, and disruption to networks of support and belonging2. It is worth mentioning that representations of climate change in the media and popular culture can also influence a person’s stress response and mental well-being.

Eco-anxiety: a reasonable and adaptive protection

Distress in relation to the impending threat of climate and ecological crises, is increasingly noted by mental health professionals and media and known as eco-anxiety. It is characterized by severe and debilitating worry about climate and environmental risks and can elicit dramatic reactions, such as loss of appetite, sleeplessness, and panic attacks among those affected. The guidance for mental health professionals to make diagnoses in the US does not yet include eco-anxiety as a specific condition, but the 2017 report by American Psychological Association elaborates the impacts of climate change on mental health and refers to the term eco-anxiety describing the ‘a chronic fear of environmental doom’.

Evidence suggested that most cases of eco-anxiety are actually adaptive responses to the changing climate2. Anxiety works as an evolutionary alarm mechanism that functions to keep us safe. If the perceived probability of danger is accurate and the anxiety is proportionate, then it is an adaptive advantage for survival. Our pain receptor in the same way triggers the reflexive move of our hands when exposing to fire. Framing of these psychological states as a condition can serve to create a so-called global victim mindset4. There has been an increase in media interest around eco-anxiety represents one such example, where a mostly reasonable response to this insidious humanitarian disaster is characterized as a new mental illness. Given that climate change is a serious threat to human health and wellbeing, perhaps it helps to be a little worried. Although, the lack of decisive global action on the issue could imply that we are not worried enough4.

Vulnerability to the climate stress

In the face of global challenges such as climate change, the degree of anxiety and distress varies from person to person. The risks are differentially distributed across communities and individuals. People in countries hit by disasters are likely to see increases in mental distress and the ability to recover will be determined by having efforts that promote resilience. However, even in countries not yet directly affected by devastation due to climate change, there are numerous personal and clinical accounts of subclinical depressive emotions, despair, and guilt associated with the climate crisis and other global environmental issues. A key factor that contributes to climate anxiety is knowing danger is coming but not having any appropriate scripts, skills, or direct agency in place to mitigate it4. There are special subgroup population that are at higher risk for negative mental health consequences from climate change issues, including children, pregnant and postpartum women, people with pre-existing mental illness, people who are economically disadvantaged, those who are homeless and first responders to the disaster4.

Negative mental status from climate change even occurred on professionals working in the field. A marine biologist at the University of Exeter studying the life in Great Barrier Reef in Australia, was reported to have suffered from the anxiety due to his work that documenting the rapid declining of ecology. The anxiety also manifests itself in physical ways like insomnia and heart palpitations5. Although this narrative has been popularized in media reporting, the evidence on the unique mental health risk climate scientists themselves face remains anecdotal. Researchers still highlight the more optimistic perspective that there are equally good reasons to think that climate scientists benefit from unique protective factors, in particular the social support and experience of collective action that comes from being involved in this research community6.

Figure 30.2 – Marinel Sheu / NBC News

From anxiety to action

How people react to their anxieties related to climate change? Researches on mental health and climate change revealed that not everyone reacts with motivation and decisive action when faced with eco-anxiety. For some, the ominous reality of climate change results in feelings of powerlessness to improve the situation, leaving them with an unresolved sense of loss, helplessness, and frustration. For others, the anxiety they have can become debilitating. Many psychological barriers often immobilize individuals with intentions to climate change mitigations and adaptation, including limited cognition, ideology standpoints, mistrust and denial4. In particular, human brains evolved to confront immediate issues not the future ones like climate change, which lead to undervalue the risk or discount personal risk of the planetary crisis. We are also influenced by the social activity structures and thus expect others to take the responsibility (e.g. technology-solution providers) and to act first (i.e. individual actions depend on social network and norms)4.

On the other hand, global society and health-care systems are not all equally equipped to deal with mental health issues related to climate change such as eco-anxiety. In particular, integrating mental health service is in need for counties currently experiencing direct disasters due to climate change (e.g. loss of homeland) and for people in low socioeconomic status.

Last but not least, one way to reduce our anxiety of climate change is to take action. Though painful, mental distress will be part of the journey.

Reference:

- Clayton, S., Manning, C., & Hodge, C. (2014). Beyond storms & droughts: The psychological impacts of climate change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica.

- Clayton, S., Devine-Wright, P., Stern, P. C., Whitmarsh, L., Carrico, A., Steg, L., … & Bonnes, M. (2015). Psychological research and global climate change. Nature Climate Change.

- Verplanken, B., & Roy, D. (2013). “My worries are rational, climate change is not”: habitual ecological worrying is an adaptive response. PloS one.

- Ingle, H. & Mikulewicz, M. (2020). Mental health and climate change: tackling invisible injustice. Lancet Planetary Health.

- BBC Three (2019). ‘Eco-anxiety’: how to spot it and what to do about it.

- Nature Climate Change(2018). Focus on climate change and mental health. Nature Clim Change.

Media Attributions

- SDG_Chapter2_Mental_Health_Figure1

- SDG_Chapter2_Mental_Health_Figure2