Karim Clivaz

Contrary to popular belief, the world’s population is not growing exponentially. In fact, since 1960, growth has been closer to being linear, following a rate of about one billion every 14 years (1). This knowledge therefore challenges Malthus’ theory, but it does not solve the problems he highlighted. The Earth and its resources are limited. This, coupled with growing environmental concern, raises several worrisome questions. Will we reach the limit of our planet’s capacity? Will we be able to feed everyone? Should births be regulated, as was the case in China?

Population growth:

The growth of a population, defined by the growth rate, is essentially determined by subtracting the mortality rate from the birth rate. To simplify the explanation, immigration and emigration can be neglected or incorporated into the previous variables. Demographic studies typically identify 4 stages in the development of a population: Stage I is characterized by a high birth rate compensated by a high mortality rate. This level of development is typically found among hunters and gatherers / in pre-industrial times. Stage II sees the mortality rate decrease due to improvements in food supply and hygiene. This period is synonymous with high population growth as we have seen in developing countries in recent history. Stage III is currently observable in many developing countries, characterized by a declining birth rate due to access to contraception, education, urbanization and social security. Finally, Stage IV would correspond to what can be observed in most European countries, the United States, Canada and Japan. Birth and death rates are low, sometimes giving way to a negative growth rate (2). These observations seem to indicate, and this is consistent with current data, that the growth rate at the global level is declining. However, caution should be exercised because a decline in the growth rate does not indicate a decline in the world population but only a decline in the rate at which the world population is growing, which is normal to observe in linear growth. This approach is useful for understanding the dynamics of demography on a large scale, but it is also important to note that it is subject to oversimplification of reality. As proof, a 2009 study even seems to indicate that above a certain threshold of development, a reversal of fertility decline can be observed (3).

Modelling:

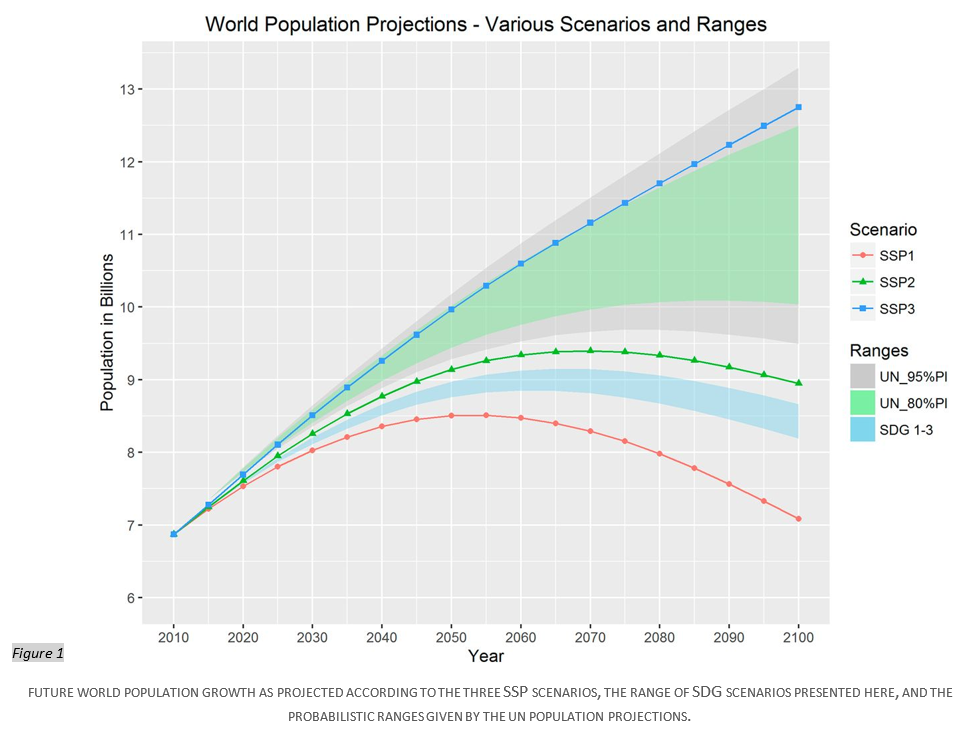

World population growth depends on many parameters, such as economic, social and health. In addition, there are uncertainties related to climate change and environmental degradation. Because of the number of variables involved, model building is difficult and predictions for the end of the century are not very accurate. Probabilistic projections of the United Nations Population Division in 2015 show a 95% prediction interval between 9.5 and 13 billion in 2100. While in the context of the IPCC, more recent scenarios considering different societal developments better known as Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) predict for both extremes 7.1 and 12.8 billion (4). This discrepancy between the different scenarios shows us how difficult it is to predict population growth at the global level. For the same reasons, it also makes it difficult for governments to make appropriate decisions.

Environment and Health:

Despite these uncertainties, most scenarios predict an increase in world population for several decades to come and there is no doubt that the world population growth will have an impact on the environment. To accommodate more people, urban areas will grow and to feed them, more agricultural land will be needed. On top of that, there is the impact that each person has directly or indirectly on the environment through their actions and consumption. However, the level of this impact remains difficult to predict given the uncertainties of growth models. Furthermore, a study based among others on the World Health Organization (WHO) reports shows that: “A growing number of people who lack basic needs, such as access to clean water and food, are more susceptible to diseases driven by malnourishment, and overpopulation, and air, water, and soil pollutants, further stresses humans and increases disease prevalence.”. It should also be noted that climate change seems to reinforce this effect, by creating an environment conducive to the spread of certain diseases that can affect not only humans but also crops (5).

Regulating births:

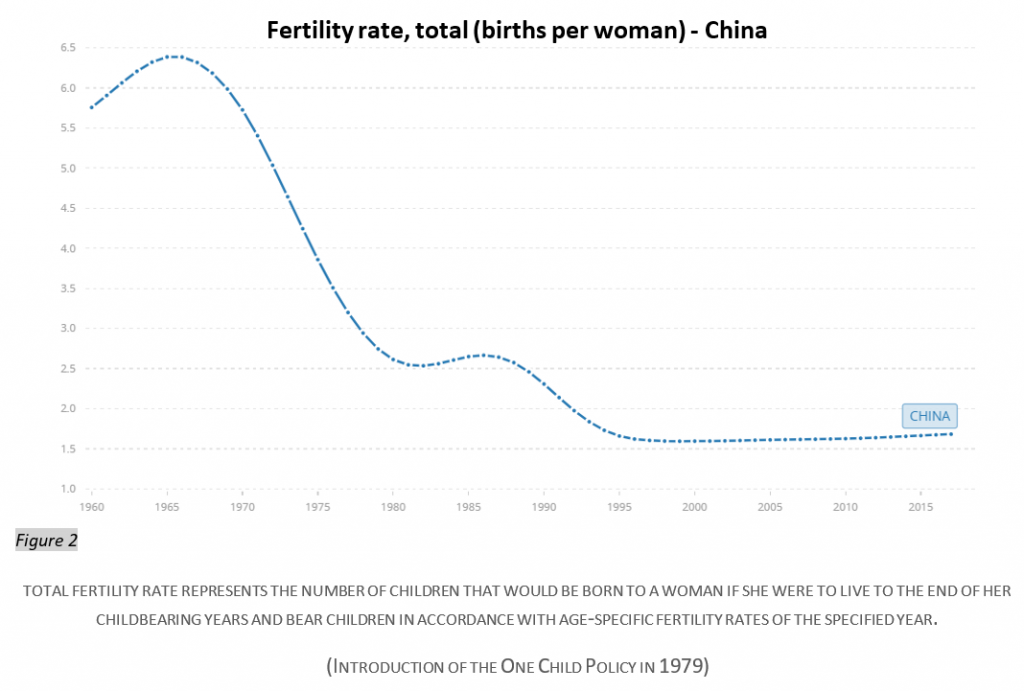

Faced with the danger of overpopulation, birth control appears to be a simple and effective way to lower the growth rate. The effectiveness of this method is not to be questioned, but as the one-child policy in China has shown us, it can have serious consequences. Such measures would increase the number of cases of infanticide, baby abandonment and human trafficking. Depending on the culture, there could also be an imbalance between girls and boys, with one sex being favoured over the other, which would run counter to SDG No. 5 (Gender equality). Apart from these consequences, such regulations also pose an ethical problem. Limiting the number of children per couple can be seen as an infringement of the fundamental right of the family and thus of the right to free procreation. Such a deprivation of liberty would meet with the opposition of a significant part of the population and thus constitute an oppressive policy, which is not desirable. A law similar to the one-child law therefore does not seem to be an appropriate measure to address this problem. Since more extreme end-of-life measures are not ethically feasible, if a policy is to emerge, it will have to be more indirect. In this sense, increasing child-related costs would be a more acceptable method. The latter would certainly be effective in developed countries, where childbearing is a choice and not a need. But there are still countries in the world (particularly in Africa) where child mortality rates are high, and children are needed to improve the quality of life. In these countries, such measures would have little or no impact.

SDGs and population growth:

Among the 17 Sustainable Developments Goals, there is no specific one on population growth, but SDG 3 (Good health and well-being) contributes indirectly to it. One of the objectives of SDG 3 is to reduce the infant and maternal mortality rate and, more generally, to increase life expectancy. Improvements in these targets have an impact on mortality, fertility and thus on population growth. Studies also show the importance of education on the mortality rate and fertility of the population, particularly among women. More educated women tend to experience lower fertility and lower child mortality. “This relationship has been corroborated recently (a), and the case has been made that improvements in female education have functional causality on declining fertility (b). It has been shown that, even under identical sets of education-specific fertility trajectories, different education scenarios alone can induce a variation of more than 1 billion in the size of the total world population by midcentury (a)”(4). This article therefore shows us that by achieving the most relevant SDG targets in the field of health and education, it would be very likely to observe a decline in fertility, particularly in countries in demographic transition.

Discussion:

This brief analysis, together with current data, seems to indicate, not too surprisingly, that the world population has not reached its peak and will therefore continue to grow. We should also note that predictions in this area are very complex and therefore leave room for many scenarios, the differences of which can be counted in billions of human beings. At this time, when climate change and its consequences are increasingly being felt, the probable increase in the future population, coupled with the lack of response by governments to this crisis, leaves a great deal of doubt as to our ability to solve our current problems and those of the future. A short research study in the field of birth control seems to provide solutions that are neither desirable nor sustainable. Despite these rather pessimistic findings, the Sustainability Developments Goals find here one more reason to be put forward. By improving health and hygiene, developing education, especially for women, it is likely that the SDGs will have a positive impact on fertility decline. It is important to specify here that such observations will only be significant if the objectives that have been set are achieved. This observation is also valid for the rest of the SDGs, and as seen above, the different Goals are not independent of each other. By improving the environment or the access to vital and health needs progress in all areas could be observed; this would most certainly have a positive impact on demographics as well as on many other areas.

References:

(1) Rosling Hans, 2015, Why the world population won’t reach 11 billion, THINK Global School,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2LyzBoHo5EI

(2) Bonhoeffer S., 11.22.2018, Lecture “Umweltsystem I” at the ETH Zürich on «Bevölkerungswachstum».

(3) Myrskylä, M., Kohler, H.-P., Billari, F. C. ,2009, Advances in development reverse fertility declines. Nature, 460, 741–743.

(4) Guy J. Abel, Bilal Barakat, Samir KC, and Wolfgang Lutz, 2016, Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals leads to lower world

population growth, PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Volume: 113 Issue: 50 Pages: 14294-14299.

a) Lutz W, S KC, 2011, Global human capital: Integrating education and population. Science 333(6042):587–592

b) Lutz W, Skirbekk V, 2014, How education drives demography and knowledge informs projections. World Population and Human Capital in the 21st Century, eds Lutz W, Butz WP, S KC (Oxford Univ Press, Oxford, UK), pp 14–38.

(5) Pimentel, D., Cooperstein, S., Randell, H. et al., 2007, Ecology of Increasing Diseases: Population Growth and Environmental

Degradation. Hum Ecol 35, 653–668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-007-9128-3

Figure 1 cf. (4)

Figure 2 Source: (1) United Nations Population Division. World Population Prospects: 2019 Revision. (2) Census reports and other

statistical publications from national statistical offices, (3) Eurostat: Demographic Statistics, (4) United Nations Statistical

Division. Population and Vital Statistics Reprot ( various years ), (5) U.S. Census Bureau: International Database, and (6)

Secretariat of the Pacific Community: Statistics and Demography Programme.

License : CC BY-4.0