Lea Fabritius

20% of global land is degraded with industrial agriculture contributing significantly to this trend (Verena Seufert, 2017). Agriculture is responsible for 22% of global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. This is linked to fertilizer production, deforestation and animal feed production. Fertilisers and pesticides pollute oceans, rivers, lakes and our drinking water resources. A tremendous biodiversity loss can be observed. The negative impact most of our agricultural systems have, not only on the environment but also on human health, is immense. Already current generations suffer under these circumstances. Taking all these burdens into account in 2015 still 795 million people suffered from hunger (Emilie A. Frison, 2016). Industrial agriculture has failed to provide a recipe for sustainable food system even though it has occupied a privileged position for decades. To stop further exploitation of nature and human beings “Business as usual is not an option anymore” (This point was expressed in the International Assessment of Agricultural Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD). Now there is an urgent need for a different model of agriculture based on diversifying farms and farming landscapes. To achieve this politic action must be undertaken (Herren, 2015).

The Pressures on our System

First, I want to spend some more words on why the time to change the established systems of agriculture is now.

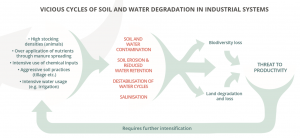

The global system regarding food security is in a precarious state due to anthropogenic pressures. Increasing net production led to less hunger as one of the main characteristics of industrial agriculture is to produce great yields and it is prised with other benefits. Once these benefits are put into a more holistic context the positive outcomes begin to shrink. The reliance of industrial agriculture on external inputs such as chemical inputs makes it vulnerable. The yield of industrial and conventional systems may be bigger than the one of more sustainable ones, but it leads to degraded soil and destroyed ecosystems. On a larger scale, over-production and waste on nature’s costs does not lead to larger yields or profit and sooner or later there is a price to be paid for every increase in productivity achieved on this basis. Considering the externalities, which come with industrial agriculture continuing likewise can in no way be sustainable. This cycle is illustrated in figure 1. It is difficult to measure the human health risks and the loss in ecosystem-richness in yields or money, but these clearly are immense costs (Emilie A. Frison, 2016).

Figure 1 Vicious cycles of soil and water in industrial systems (Emilie A. Frison, 2016)

Driving sustainability in agriculture and food systems would have positive effects on several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): SDG 1, No Poverty; SDG 2, Zero Hunger; SDG 3, Good Health and Wellbeing; SDG 6, Clean Water and Sanitation; SDG 12, Responsible Consumption and Production; SDG 13, Climate Action; SDG 14, Life below Water; and SDG 15, Life on Land (Frank Eyhorn, 2019).

It is obvious, a change must be made. Research is being done to find opportunities for more sustainable systems. These systems need to be able to provide enough nutritious food for all and at the same time minimize environmental and human impacts (Frank Eyhorn, 2019). But is there a perfect solution? Uniformity in food systems is a huge problem. Learning from the past we can conclude that a “one size fits all” approach does not work as a long-term solution. Roughly it can be said we need a shift to more diversified systems, which replace chemical inputs and increase biodiversity like agroecology and organic farming concepts. The basis for new solutions already exists, but the real difficulty is to implement them on a larger scale. The implementation of new systems is the crucial step, which must be accompanied by further improvements and adoptions to the preconditions. The efforts made in agroecology concepts are stunning considering that there is far less investment made in this section (Emilie A. Frison, 2016). The situation in Sikkim is example on how changes can be made.

Welcome to Sikkim

A small Indian state called Sikkim sets an example and proves that 100% organic agriculture can be possible. Shri Pawan Chamling, prime minister of Sikkim, had this vision more than 15 years ago and not seldom he was called a dreamer. He wanted to free the country from dangerous chemicals and thereby protect human health and ecosystems. Several years later he implemented his vision successfully in the whole state.

He says himself the way until today has been long and difficult. There are a lot of small farms in Sikkim and all farmers had to be convinced and introduced into a new farming system. Shri Pawan Chamling says that even more difficult than convincing the farmers of his vision was to get the support of institutions and the bureaucracy. Especially the agriculture department and its minister did not believe that such a transition was even possible. As Sikkim was the first state to implement such an ambitious objective there were no templates and strategies of other states, which could be adopted. They had to reinvent the wheel from the very beginning.

By shortening the states subsidies annually by 10% chemical fertilisers were made unattractive. This lowered the interest of the farmers in a great extent. Farmers were instructed into the organic farming system and certifications following international standards were established. Chamling went even further by prohibiting the import of conventional vegetables and fruits. He generated incentives and paved the way to make the shift from conventional to organic farming more convenient und lucrative. This approach seems to be a success. The people in Sikkim are proud to be farmers and the environment profits alongside. 30% of the land is now declared national park and conservation area. Chopping of trees is forbidden. If you do so you must plant ten new trees. The energy supply is 100% renewable (solar- and waterpower) and it is even being exported. To avoid plastic, water is only served in glass bottles.

His mission has by no means yet come to an end. It goes far beyond the borders of Sikkim trying to spread organic agriculture even further. This little country is extraordinary, and its rules and efforts can’t be transformed easily to other and especially lager countries, but it is an example which shows what politicians with a clear vision of a sustainable future can achieve (Geier, 2019).

The Framework

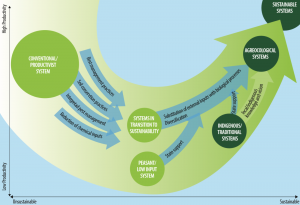

The example of Sikkim demonstrates how important political support and action is to achieve an effort in the direction of more sustainable systems. Political support is also shown as an important contributor to sustainable systems in the following figure.

Figure 2 Transition to productive and sustainable systems from various exit systems (from IAASTD 2009 – Latin America and Caribbean Summary for Decision Makers)

Big changes cannot be made on a voluntary basis only. At the moment there is not sufficient broad-based political support. Regulatory frameworks and economic incentives are either lacking or not being pushed enough. The actual incentives keep farmers locked into unsustainable structures and logics rather than encouraging them to go a step further. To get them motivated to try something new and to strengthen emerging opportunities vicious cycles that keep industrial agriculture into place must be broken (Emilie A. Frison, 2016).

Policies aligned with the SDGs could help to promote the transition. The SDGs give an already existing framework to reconsider the sustainability of different farming approaches and built a basis for helping policies as well. Policy interventions are supporting transformative systems by stimulating a pull effect on an increasing market demand for sustainable products or ruling out unsustainable practices.

Buthan and some Indian states try to achieve a 100% conversion to organic land area and countries like Germany, Austria and Finland are implementing action plans. Similar to Sikkim their strategies address several fronts. The interconnection of demand and supply provides some scope to combine several measures. Push measures include research support and advisory services, pull measures try to stimulate consumer demand and enabling measures deal for example with data collection (Frank Eyhorn, 2019). The interconnection of demand and supply provides some scope to react differently to the issue.

Swiss people spend only 6.4 % of their income on nutrition and there is a widespread expectation for cheap food [1]. If wheat is cheaper than gritting material used to secure roads during winter the proportion does not seem to be right. How can it be justified to promote an increment in production while tons of food are wasted or lost during production at the same time [2]. Food is more than just a commodity; we greatly depend on it. Thus, it should be reliable, sustainable but also valued.

Promoting the demand for sustainable products can be done by raising the awareness on the impacts of agriculture on environment and health. True pricing must be made by taking destructive impacts (on soils, water, pollinators, biodiversity, human health) of industrial agriculture into account. Shifting subsidies from conventional agriculture to sustainable agriculture organic products would get affordable to a broader range of consumers. To achieve larger impacts also retailers must be addressed and convinced to offer more sustainable products and discounting others. (Frank Eyhorn, 2019).

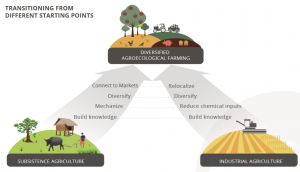

To summarize sustainable agriculture must be a priority in political objectives and even further it must be the aim of whole states and become its missions too. We need a global transition and one of the biggest difficulties is that there is no unique global solution, which could be implemented in every country. There are various measures and starting points but listing them all would go beyond the scope of this text. The following graphic shows how an approach could look like.

Figure 3 Transition from different starting points (Emilie A. Frison, 2016)

The point is that a regulatory framework should be set by governments. They can no longer see this issue as acceptable collateral damage, because until now pace of reforms is insufficient for meeting the SDGs by 2030. There is great opportunity for agriculture becoming part of the solution contributing to a sustainable system within planetary boundaries rather than to intensify the problem.

As always change comes with a shift in mindset and it needs time. There are several ways to foster this shift, but the final step must come among individuals themselves.

Sources

Emilie A. Frison. (2016). From Uniformity to Diversity: a paradigm shift from indusrtial agriculture to diversified agroecological systems. . International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food).

Frank Eyhorn, A. M.-H. (2019). Sustainability in global agriculture driven by organic farming. Nature Sustainability.

Geier, B. (Februar 2019). Wilkommen in Sikkim. Neue Gentechnik-Die grosse Versuchung , S. 48.

Herren, H. ,. (2015). Feeding the People: Agroecology for nourishing the world and transforming the agri-food system. IFOAM EU Group.

Verena Seufert, N. R. (2017). Many shades of gray- The context-dependent performance of organic agriculture. Science advances.

[2] Documentation “We feed the world movie” by Erwin Wagenhofer

Media Attributions

- Vicious cycles of soil and water in industrial systems

- Transition to productive and sustainable systems from various exit systems (from IAASTD 2009 – Latin America and Caribbean Summary for Decision Makers)

- Transition from different starting points