Kiarash Kyanian

Whilst the COVID-19 pandemic is currently rippling through the world and crippled some of the worlds largest metropolises like New York and London the reprieve it has provided for the natural world and climate have been a foil to what many consider to be the existential crisis wake of our times. Only in the future will we know whether this incredible event will have altered our global zeitgeist in such a manner to adopt meaningful long term positive changes to preserve our climate. The question now is will a pheonix rise from the ashes or a wasteland of lost opportunity?

“A heap of broken images, where the sun beats, And the dead tree gives no shelter … I will show you fear in a handful of dust” – T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land

Economists have coined the term the “Great Lockdown” to describe what they predict to be the greatest economic crisis since the Great Depression; the COVID-19 cris. Climate science and the social science of Economics are closely related and this current COVID-19 pandemic sweeping the world has had devastating implications on economic growth. Notably however in the short term the natural world is experiencing a well deserved period of reprieve from the pressures of industry and the never-ending pursuit of growth. Although the short term benefits for the climate are clear the COVID-19 pandemic is unlikely to make any real long term ground in helping the global economy meet its Paris Climate Accord targets. Indirectly however the pandemic has highlighted and subverted many of our key values both in the economic (i.e. the Ricardian economic model which lends itself to the interconnected global economy and international supply chains) and social spheres. Ultimately it’s unlikely that this pandemics implications will have any long-term benefit for the climate.

Figure 49.1 – Falls in nitrogen dioxide levels as a result of the locdowns – (World Economic Forum, 2020)

In the short term the COVID-19 pandemic has had a dramatic positive impact on the climate and environment around the world. The “Great Lockdown” has as expected had a dramatic short term impact on the day to day lives of people subduing consumer confidence and demand in all economies and ergo dampening economic growth and thus production. (Ghosh, 2020)

With people in lockdown we have observed a 70% reduction in road traffic in the UK, global air traffic has reduced by over 50% with similar trends being seen globally. We have observed China’s carbon emissions fall by 18% and a fall of between 40-60% within Europe. (The Guardian, 2020). This rudimentary description does in fact point to the broader correlation that exists between economic growth and carbon emissions. The image to the right shows in two separate cases the fall in NO2 levels as a direct result of the lockdowns.

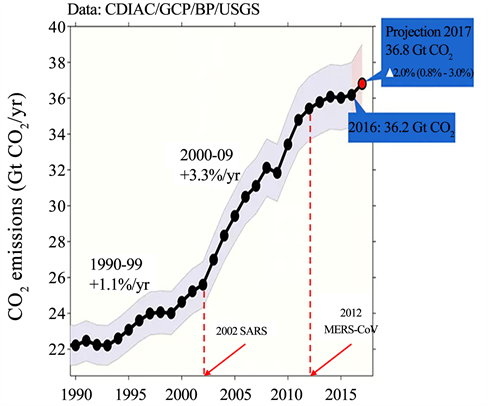

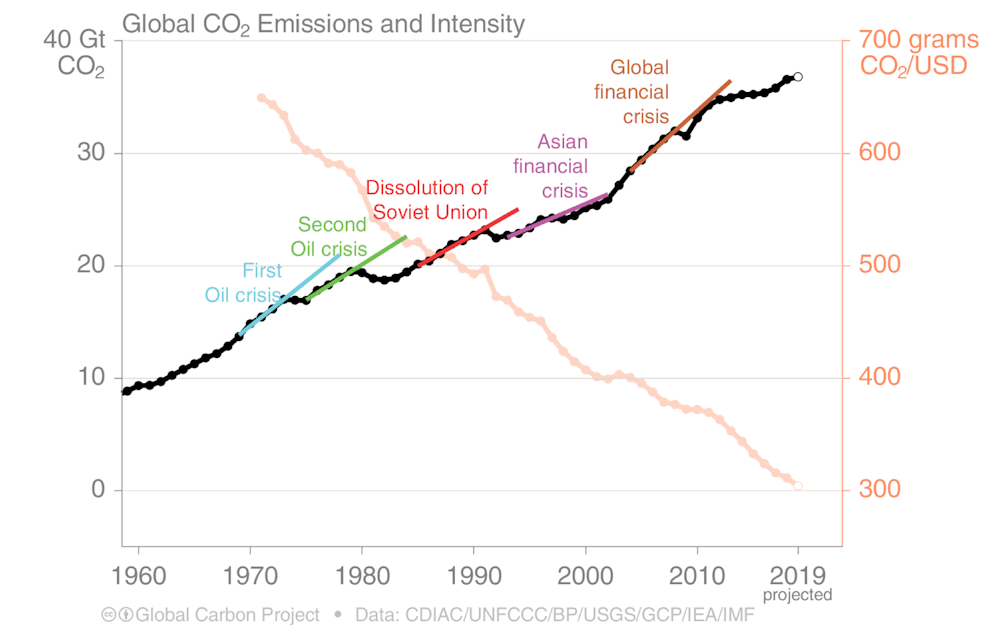

In the long-term it is likely that COVID-19 will itself have no direct impact on climate change or CO2 emissions. The phenomena of the ‘emissions rebound’ has been cited by many and refers to the large fiscal stimulus packages implemented by governments to help their economies recover from the economic fallout of financial crises. Geopolitical, financial and even other health crises have seen emissions be delayed for at most a few years or plataue but inevitably it seems that emissions return as seen clearly in the graphics below.

Biodiversity has also benefitted in the short term from the “Great Lockdown” with vast swathes of land which had previously been bustling metropolises and other urban areas having a drastically reduced human presence we have seen images of animals re-enter these areas (Corlett, et al., 2020). The aforementioned reduction in air pollution has also resulted in drastically improved visibility with a commonly referred to example being that the Himalayas are visible from India for the first time in 30 years (McLaughlin, 2020).

Despite the fact that in the short term the migration of animals has been unobstructed by human activity in the long term the greatest potential benefit arising in the wake of this pandemic will be the significiant reduction in the global wildlife trade. According to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) ¾ of emerging infectious diseases come from animals (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017) with one of the major mechanisms for their transmission being the wildlife ‘wet’ markets which have been linked to SARS (RG, 2004) and currently COVID -19.

In response to the current pandemic China has in fact stopped its wildlife trade however a similar move was made during the SARS epidemic and reversed soon after. As aforementioned the noise, pollution and other detrimental impacts which the natural world has had a reprieve from recently will rebound after the pandemic is over. However, COVID-19 has brought the relationship between human activity and biodiversity to the social conscious.

“Experts in emerging infectious diseases have been warning for decades that habitat fragmentation and degradation, and live animal markets, increase the risk of diseases spilling over from wildlife into human populations. The emergence of many of the new scourges of our time—HIV, Ebola, Nipah, SARS, H5N1 and others—can be attributed, at least in part, to increased human impacts on natural systems. ” – (Corlett, et al., 2020)

Only time will tell if peoples, societies and governments will take a stand in preventing a return to the status quo and fight to protect their newly cleaned environments and climate. Perhaps this pandemic will serve to cure the virus of mankind from continuing to molest the natural world.

References:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017. Zoonotic Diseases. [Online]

Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/zoonotic-diseases.html

[Accessed 18 April 2020].

Corlett, R. T. et al., 2020. Impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on biodiversity conservation. National Center for Biotechnology Information, 8 April.

Ghosh, I., 2020. Visual Capitalist. [Online]

Available at: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/coronavirus-lockdowns-emissions/

[Accessed 18 April 2020].

Kim, T.-J., 2019. Spanish Flu, SARS, MERS-CoV by CO2 Emission and Maximal Sunspot Number. Scientific Reasearch, January, 12(1), pp. 53-75.

McLaughlin, K., 2020. Insider. [Online]

Available at: https://www.insider.com/himalayas-seen-from-india-pollution-drop-coronavirus-lockdown-2020-4

[Accessed 19 April 2020].

Peters, G., 2020. How changes brought on by coronavirus could help tackle climate change. [Online]

Available at: https://theconversation.com/how-changes-brought-on-by-coronavirus-could-help-tackle-climate-change-133509

[Accessed 18 April 2020].

RG, W., 2004. Wet markets–a continuing source of severe acute respiratory syndrome and influenza?. National Center for Biotechnology Information, pp. 234-236.

The Guardian, 2020. The Guardian. [Online]

Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/12/the-guardian-view-on-the-climate-and-coronavirus-global-warnings

[Accessed 18 April 2020].

World Economic Forum, 2020. These satellite photos show how COVID-19 lockdowns have impacted global emissions. [Online]

Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/03/emissions-impact-coronavirus-lockdowns-satellites/

[Accessed 18 April 2020].