Vera Stäheli

Figure 54.1 – Blacktip reef shark, Viti Levu Fiji. Picture taken by Patricia Zwolinski

Ocean acidification is becoming a more and more urgent topic, related to the problematic effects of climate change. Marine ecosystems are about to change drastically due to rising CO2 levels and the correlating decrease in pH values. Exemplified by observing shark behaviour under CO2 levels projected to the end of this century, it can be demonstrated how the hierarchy of marine life will fall out of balance with consequences that effect not only oceanic habitats but also terrestrial life.

Today, more than 200 years after the industrial revolution, climate change is a topic concerning the whole world. While many actively try their best to make a change, others nod their head distantly and some still believe it’s just a myth, at least everyone has heard of the rising CO2 levels in the atmosphere. Greenhouse gas emissions, ozone depletion, rising temperatures leading to more wildfires are all frequently discussed topics when it comes to climate change, but do you recognize a pattern? They all mainly refer to terrestrial habitats. Although coral bleaching and ocean acidification are rising topics, most people cannot really relate anything to it.

Anthropogenic emissions have driven atmospheric CO2 concentrations to over 400 ppm, which is higher than they have ever been in the past 800’000 years. Predictions show no sign of stagnation, if the current trajectory is maintained it is expected to exceed 900 ppm until 2100. Levels would be even higher if it were not for the absorption capacity of the oceans, which absorb almost a third of global CO2 emissions [1]. But this too comes with a price, the uptake of additional anthropogenic CO2 has reduced average pH values by 0.1 units since preindustrial times and will decline by further 0.3-0.4 units until the end of the century [2]. Upon mixing, water (H2O) and CO2 form carbonic acid (H2CO3). By definition, acids release hydrogen ions (H+), rendering the solution they are in more acidic, which is indicated by a decrease of the pH value. The effects of this ocean acidification are most commonly discussed in terms of coral bleaching, as carbonate ions (CO32- ) become less available at lower pH values, which are important for building and maintaining the coral skeleton [3]. Only recently though, the impact of a more acidic marine environment on water-breathing organisms, such as Teleostei (bony fish) and Elasmobranchii (sharks, skates and rays) are being investigated. Rising CO2 levels do not only acidify the ocean, but also the blood and tissues of said marine life. Several studies show significant behavioural changes of marine fish due to CO2 increasement, impairing olfactory sensing, decision-making and other important biological processes [4].

Why should we care?

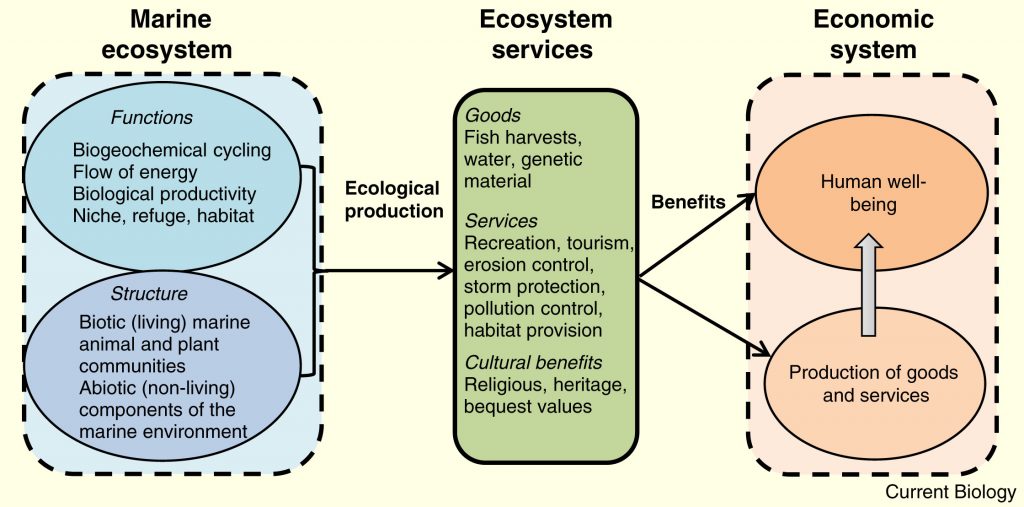

As apex predators, sharks play a major role in marine ecosystems. They are a so called “key-stone” species, keeping everything below them in the food chain at balance, regulating species abundance, as well as keeping predatory species genetically healthy and removing diseased and sick individuals. All this contributes to keeping their ecosystems healthy and functional [5]. In contrast to most other marine fishes, Elasmobranchii are k-strategists which means they have slow growth, late maturity, low fecundity and only few offspring. These traits make them extremely vulnerable to any rapid changes in their environment and sets them at risk of being easily overfished [2]. According to IUCN (International Union for Conversation of Nature) a quarter of the world’s elasmobranch species are threatened with extinction [6]. Further decrease of their populations will have cascading effects on marine ecosystems, which will in turn also impact terrestrial ones. For example, the loss of sharks leads to overpopulation of algae which can cause harmful algal blooms (HABs). HABs can produce toxins, killing fish, mammals and birds as well as causing illness or even death in humans. Other non-toxic blooms can severely lower oxygen levels, making entire zones inhabitable for fish and plants [7]. Especially in coastal areas marine ecosystems provide important services, such as storm protection e.g. mangrove forests, which are also imperative protection areas for juvenile sharks, pollution and erosion control, but also have economical benefits, being an important food source, touristic attraction and transportation mode [8].

Figure 54.2 – Beneficial impacts of marine ecosystems on human economic system [8]

Elasmobranch fishes have a far superior olfactory sensitivities compared to teleost fishes, as well as an elaborate electroreceptor system, consisting of so called “ampullae of Lorenzini”, which are extremely sensitive to electrical fields, allowing geomagnetic navigation and detection of other fish’s bioelectrical fields [9]. These two characteristics are essential for the survival of these species at the top of the food chain. Studies have now shown that sharks exposed to elevated CO2 levels exhibit sensory and behavioural abnormalities. Change in behaviour of these predators will then again have fundamental impact on prey species [10].

Ocean acidification simulations

A study done by Dixon et al. in 2014 analysed the effect of rising CO2 levels on the odour tracking ability of the smooth dogfish shark, Mustelus canis. The sharks were either kept at medium or highly elevated CO2 levels, corresponding to the projections for 2100, as well as at current-day level as a control. The sharks’ behaviour towards concentrated squid rinse as prey odour was then observed in choice flumes. As expected, the control sharks would readily swim towards the prey stimuli, spending more time in the area where the squid rinse was added. While the sharks kept at medium levels CO2 still showed this natural behaviour, the animals kept at high levels did not only seem to ignore the stimuli, but actively avoided it when added to their preferred swimming side of the flume. These results suggest that elevated marine CO2 levels could drastically change predator-prey interactions if anthropogenic emissions are not kept at bay [10]. It is important to remember that the CO2 concentrations used in this study are not just randomly picked high values, but values that will without doubt be reached within the next 80 years if there is no substantial change in human efforts.

Looking into the future

Sharks have inhabited this planet for 450 million years, which is 200 million years before dinosaurs roamed the world and another 35 million years after they had become extinct. In this time sharks have survived 5 mass extinctions and periods of high CO2 levels in the geologic past, which were much higher than the increase we are currently causing. Yet, we cannot rely on their adaptive capacity to keep pace with the current unprecedented velocity with which the composition of marine environments is changing [10]. What are 80 years in comparison to periods of millions of years? It is this extreme imbalance of time spans we have to be aware of when talking about changing CO2 levels, or any changes regarding environments everywhere around the globe. In addition to the stress resulting from pollution, many species also face increasing pressure from overfishing and habitat loss, further lowering the chance of successful adaptation to the anthropogenic era.

To protect sharks and many other species, marine as well as terrestrial, from going extinct, change has to happen now, and it has to happen fast. The solution seems obvious: reduce carbon emissions, stop overfishing and prevent habitat loss. Where it gets tricky is in the execution of these intentions. With the evermore growing human population on this planet it is illusive to think we will be able to reduce our emissions that drastically. People will continue to consume internationally produced goods and travel the world, which is also necessary to keep the global economy healthy. Just think of the coastal regions for which marine ecosystems bring so many beneficial services, these would be the ones most affected. Taking overfishing as parade example, many communities rely on the money coming from fish harvests and do not have the possibility to give that up without financial support. Therefore, it is crucial for the whole world to cooperate, areas affected most by restrictions have to be provided assistance by the regions not directly associated with whatever measure is put into action.

Imperative for action

In order to achieve a sustainable lifestyle and further development we are now more than ever dependent on new technologies providing alternative energy and food production. These innovations are not something we have yet to come up with, as there are already many successful projects such as the ETH invention “Syngas”, a CO2 neutral fuel made out of air and sunlight [11]. What is needed now is the implementation of these innovations in an economically feasible way, which can only be achieved in a global understanding and political coordination.

References:

| [1] | „World Economic Forum,“ [Online]. Available: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/03/oceans-do-us-a-huge-service-by-absorbing-nearly-a-third-of-global-co2-emissions-but-at-what-cost . [Accessed 11 April 2020]. |

| [2] | R. Rosa, J. Rummer und Munday, „Biological responses of sharks to ocean acidification,“ Biology Letters, Bd. 13, 2017. |

| [3] | „National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration,“ [Online]. Available: https://www.noaa.gov/education/resource-collections/ocean-coasts-education-resources/ocean-acidification. [Accessed 10 April 2020]. |

| [4] | P. Munday, D. Dixson, M. McCornmick, M. Meekan, M. Ferrari und D. Chivers, „Replenishment of fish populations is threatened by ocean acidification,“ Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA, Nr. 107, pp. 12930-12934, 2010. |

| [5] | „White Shark Projects,“ [Online]. Available: https://www.whitesharkprojects.co.za/news/the-importance-of-sharks/ . [Accessed 10 April 2020]. |

| [6] | „IUCN,“ [Online]. Available: https://www.iucn.org/content/a-quarter-sharks-and-rays-threatened-extinction. [Accessed 10 April 2020]. |

| [7] | „National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration,“ [Online]. Available: https://www.noaa.gov/what-is-harmful-algal-bloom. [Accessed 14 April 2020]. |

| [8] | „Science Direct,“ [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982217302890. [Accessed 11 April 2020]. |

| [9] | „Science Direct,“ [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/ampullae-of-lorenzini. [Accessed 10 April 2020]. |

| [10] | Dixson, D. &. Jennings, A. &. Atema, J. &. Munday und Phillip, „Odor tracking in sharks is reduced under future ocean acidification conditions,“ Global change biology , Bd. 21, 2014. |

| [11] | „ETH Zürich,“ 13 06 2019. [Online]. Available: https://ethz.ch/de/news-und-veranstaltungen/eth-news/news/2019/06/mm-solare-mini-raffinerie.html. [Accessed 13 April 2020] |