Stella Harper

Hold on. Take a second and be aware of the actions you are taking in this very moment: You are breathing, your mind might be wandering, and your eyes glance at letters that form words and bring a sense of meaning to your brain. Letters make words and create meaning. Creating meaning holds power- the power to use information to make individual decisions. The act of reading comes to most of us as easily as most daily actions. However, we are hardly aware of what a privilege this act of reading truly is. At the present time 750 million2 adults remain illiterate and 617 million 3 children have not reached a minimum proficiency in reading, and this in a world where most education is based on written information.

Reading is an ability that many of us grew up with and take for granted. While we were snuggled in bed safely, our parents would read aloud a story of a chubby, yellow bear and his animals friends going on adventures. Reading at this point, was experienced as a pleasure, even before it started becoming a source for fulfilling intellectual curiosity. When the school age was finally reached, a step-by-step process followed. Fictional stories and children books expanded to a source of information that opened the world of education to each individual. This also opened a world of freedom to learn, understand and communicate. As the writer Frederick Douglass put it :

“Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.”

Tragically, this freedom is not accessible to 750 million adults who at the present time still remain illiterate. Two thirds of these are women 2, a shocking statistic. This also could have a large influence on the illiteracy of their children.

The SDGs as a Step in the Right Direction

As the Global Sustainable Developement Report 20191 claims, the least-developed countries are the most affected. Besides the many other development issues and problems that exist in what we call the global south, illiteracy is one that can hinder all areas of development, on an individual as well as on a communal scale. A key factor of sustainable development is education, which means the ability to read and gain access to information. So how are we able to focus on education in the less-developed countries when the basic element for this is not given to people equally?

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly the goal 4, tries to tackle the answer to this question in all its complexity. The SDGs were created as a response to the Millennium Development Goals in the year 2015 by the United Nations to ensure a sustainable future for the coming generations. The 17 goals with 169 targets hold the power to make changes globally. Goal number 4 formulates one of these global necesseties by asking to; “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” 2 .

The underlying target, 4.6, specifically asks to achieve literacy in a substantial proportion of adults. However, solely based on this goal, many further questions arise. What defines a substantial part of a population in a world which we share with 7.7 billion other people? And how does one plan to achieve literacy both in children and adults? How will we ensure that women are granted the same privilege to learn to read?

Figure 4.2 – Goal 4 2 of the Sustainable Development Goals- Quality Education for All

Until now more questions have been asked than have been answered. In this blog I will try to make a first attempt at breaking down this complex system in order to find at least some answers for achieving and securing sustainable education.

4...1 – Bottom up, Top down

To analyze the source of illiteracy as well as the possible scenarios and implications of the Sustainable Development Goal number four, I recommend observing the goal both on a micro and a macro level as suggested by Boeren5.

The micro level can be applied to your own home situation. Based on your surroundings, your parents and your upbringing, your chance of education can differ. Most probably the largest proportion of the readers of this text have grown up with security and support in at least one, if not all of the above. However, for a large part of the world this is not the case. War, poverty, lack of infrastructure or gender equality are only some of many reasons for the lack in education in individuals. Based on an article by Lynn Clark Callister 6, countries in South and West Asia as well as the region in sub-Saharan Africa have the lowest literacy rates accounted for globally. They are also part of the regions that are most vulnerable to poverty. This creates a vicious circle, which only can be broken when a sustainable solution is found for each problematic variable. One cannot progress in education when variables such as poverty stand in the way. At the same time, education plays the dominant role in reaching economic security. Hence, other goals of the SDGs must be linked and solved together to face this challenge. Sustainable development involves many different dimensions that require a conceptual approach of their interdependancy.

The macro aspect of the situation happens on a policy-making level. Depending on the country in which one resides, different regulations exist on mandatory education. In Germany, for example, attending school until the 9-10th grade is mandatory. While sometimes students view this as being a bain in their daily lives, it is an opportunity that many do not have. In countries such as Somalia, school access is extremely limited 7. If the policy of that country could create a framework that would give children a chance to learn, education would be given the necessary priority.

Unfortunately, wherever we look in the world today multiple problems seem to appear at the political level; but it remains a governmental decision what to prioritize and which problems need more attention in solving than others. In the countries with a visibly high rate of illiteracy, education is falling short. And this is happening even though education is so important to secure a country´s welfare and sustainability for the future. It is a tragedy, with an ending that has yet to be rewritten. However, an attempt at answering the demands of the fourth Sustainable Development Gooal can help take a step towards a new story line.

4...2 – Battling the Statistics

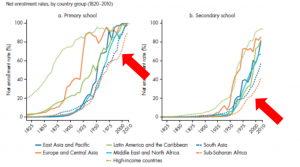

As mentioned above, often the countries that are lacking in primary school education are situated in the global south, especially in Africa. Isabel Günther, Professor of Development Economics and Director of NADEL, made clear that one has to be careful when measuring any kind of educational progress. According to Professor Günther, the positive news was that primary school enrollments have increased over the years, especially in sub-saharan Africa.

Figure 4.3 – Massive expansion of primary school enrollment8

.

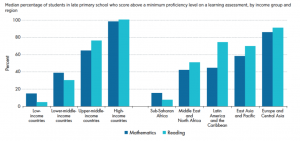

However, by examining more data one can observe that even though the access to education has been rising, the learning indicators tell a different story. The basic skill of reading (light blue bar in the graph below), based on the World Development Report of 2018 7, remains very low despite an increase in the access to primary education. This example shows the importance of analyzing statistics before intuitively reaching conclusions one hopes to attain. In addition, the importance of painting the “whole picture” gains new meaning. Primary education enrollment is a right step in “Ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education (…)”2 and therefore reaching one of the Sustainable Developement Goals, however it is linked to so much more. It is linked psychologically to the support of parents and teachers and physically through infrastructure and materials. It is linked to security and health, as well as safety and political environment. In fact, the necessity of literacy is linked to each of the seventeen sustainable development goals. This is an example of the dependency of the SDG goals on one another, and shows that the overall goal cannot be to fulfill only one of them. They have to be reached in a working combination with each other.

Figure 4.4 – Children don’t learn in schools 8

4...3 – Closer than we Think

We have been talking a lot about ensuring quality education, as it relates to literacy, by using examples that are not part of “the western world” or the “the global north”. When we talk about “we”, we automatically exclude a large part of the world. This distinction, which I would argue is an ignorant simplification of reality, focuses to the large part on the continents North America and Europe. We measure welfare and progress as defined by an indicator of development that is set by global institutions. However, are “we” really much better than this distinction we make to the rest of the world ?

Based on the arguments we have set, countries in the west should be able to tackle illiteracy through lower poverty rates, economic stability and social security. Welfare can be measured using indicators such as the HDI ( Human Development Index).

Figure 4.5 – World map indicating the categories of HDI by countries 9

As seen in the world map above, our assumption appears to be true, since the part of the map showing an extremely high human development parameter ( high = more welfare) in what we define as the global north. And this, based on everything we have discovered, should most probably correlate to low rates of illiteracy, no?

Unfortunately not. Suprisingly, the United States of America, has been fighting its own battle with illiteracy.

«Approximately 32 million adults in the United States can’t read, according to the U.S. Department of Education and the National Institute of Literacy. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development found that 50 percent of U.S. adults can’t read a book written at an eighth-grade level.»

– Washington Post 10

In a population of around 327.2 Million (2018), thirty-two million adults make up 9,78% of the population that cannot read. With this information, I am not trying to paint a hopeless picture of the world, but making the point that illiteracy or in a broader sense, education, is a global issue rather than an isolated, national one. Hence, the Sustainable Development Goals follow the right track by including all countries to ensure quality education, and not only the ones that one would intuitively suspect. It is not about “them” and “us” or about “more” or “less” developed countries. Literacy and education have to be considered in the framework of global progress in the context of a sustainable future.

4...4 – Self-Reflection

“Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.”

―

Have you learned something or gained knowledge or data from this text? Or did you only read this for pasttime purposes? However you might answer these questions, you were part of a larger experiment to support the importance of literacy for all. It does not matter if you agree with the information given or if you remember the numbers displayed or not. The significance lies in the fact that this information was made accessible to you. And the fact is, you were able to read it and make the choice to further educate yourself.

So the next time you are reading a paper- hold on, take a second- and reflect on the privilege you are enjoying in this moment: The privilege of having the freedom to experience the power of words.

Reference:

- Independent Group of Scientists appointed by the Secretary-General, Global Sustainable Development Report 2019: The Future is Now – Science for Achieving Sustainable Development, (United Nations, New York, 2019).

-

Goal 4 .:. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. (o. J.). Abgerufen 9. März 2020, von https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg4

-

617 million children and adolescents not getting the minimum in reading and math. (2017, September 30). Abgerufen 12. März 2020, von https://en.unesco.org/news/617-million-children-and-adolescents-not-getting-minimum-reading-and-math

-

Goals | UNESCO Chair on „Physical Activity and Health in Educational Settings“. (o. J.). Acessed 13. March 2020, from https://unesco-chair.dsbg.unibas.ch/en/goals/

-

Boeren, E. (2019). Understanding Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 on “quality education” from micro, meso and macro perspectives. International Review of Education, 65(2), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-019-09772-7. https://doi.org/10.1097/nmc.0000000000000504

- Callister, L. C. (2019). Overcoming Illiteracy in Women and Girls. MCN, The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 44(2), 118. https://doi.org/10.1097/nmc.0000000000000504

-

Shepherd, J. (2010, September 20). 70 million children get no education, says report. Abgerufen von https://www.theguardian.com/education/2010/sep/20/70m-get-no-education

-

Günther, I. G. (2020, März 4). The Global Learning Crisis [Vorlesungsfolien]. Abgerufen von https://moodle-app2.let.ethz.ch/mod/resource/view.php?id=422921&redirect=1

-

Rezaeian, S. R. (o. J.). World map indicating the categories of HDI by countries [Diagramm]. Abgerufen von https://www.researchgate.net/figure/World-map-indicating-the-categories-of-HDI-by-countries-based-on-data-2013_fig5_325107472

-

Strauss, V. S. (2016, November 1). Hiding in plain sight: The adult literacy crisis. Washington Post. Abgerufen von https://www.washingtonpost.com

Media Attributions

- Bildschirmfoto 2020-03-15 um 07.50.19

- Bildschirmfoto 2020-03-15 um 07.53.52