Lars Kistler

“I make sure that most of what I consume is bio and organic.” This was the slider (0-100%) for the active participation this week (Week 8). The statement suggests that consuming organic is superior to conventionally produced food. Since this course is about the sustainable development goals, the statement could be interpreted as organic produced food is better in terms of sustainability. Since many fertilizers and pesticides are restricted, it seems obvious “bio” would be the better choice from an environmental standpoint. But is this intuition true? Is organically produced food truly more sustainable than conventionally produced food? Should you indeed make sure that most of what you consume is organic?

What does organically produced food mean?

Buying organic is turning from an alternative to a moral and social responsibility. As discussed in the intro supposedly it is the superior, more sustainable choice of consuming products. But what does organic mean?

The exact definition of organic agriculture as approved by the IFOAM (International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movement) General Assembly in Vignola Italy (June 2008) is as follows:

“Organic agriculture is a production system that sustains the health of soils, ecosystems, and people. It relies on ecological processes, biodiversity and cycles adapted to local conditions, rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects. Organic agriculture combines tradition, innovation and science to benefit the shared environment and promote fair relationships and a good quality of life for all involved.” [1]

But as a matter of fact, there is no global consensus. In every region there are different rules and definitions. Producing organic in the E.U. is subject to different regulations than for example in the U.S. The common ground of these systems seems to be that organically produced food is farmed without GMO seeds, synthetic fertilizers or synthetic pesticides [2] [3] [4]. In organic farming more traditional ways of producing food are used e.g. crop rotations, organic fertilizers (compost, manure).

Why do people buy organic food?

Baudry et al. [5] ranked different first and second dimensions from score ranging 0 to 10 in their study, see table 1 .

| Ranking | Dimension | Mean ± SD |

| 1 | Taste | 8.90 ± 1.24 |

| 2 | Health | 7.68 ± 1.68 |

| 3 | Absence of contaminants | 7.66 ± 2.09 |

| 4 | Local and traditional production | 7.51 ± 1.73 |

| 5 | Price | 7.33 ± 1.91 |

| 6 | Ethics and environment | 5.85 ± 2.03 |

| 7 | Convenience | 5.48 ± 2.53 |

| 8 | Innovation | 3.53 ± 2.09 |

| 9 | Avoidance for environmental reasons | 2.79 ± 2.15 |

| Second order dimension | Healthy and environmentally friendly consumption | 7.17 ± 1.57 |

Table 1 shows the overall scores from all 22’966 participants. The higher the ranking the bigger was the reason for why they bought organic products. They clustered the participants into different sociodemographic categories according to the answers given in the questionnaire. The so called “green organic food eaters” category scored the highest in the dimension “Ethics and environment” and also scored highest in the second dimension order “Health and environmentally friendly consumption” that encompassed two main pillars of diet sustainability as described by FAO (i.e. health and environment) [6]. This category also had the highest percentage of post-secondary graduate individuals [5]. It is fair to assume that most of the SDG class correspond to this category.

Let’s have a closer look at the second order dimension “Health and environmentally friendly consumption”. This indicator consists out of the first-dimension values:

- Ethics and Environment

- Local and traditional production

- Health

- Absence of contaminants

So, if those are the dimensions/reasons why we buy organically produced food, does organic food then perform better in these categories than conventional food?

Absence of contaminants

Several studies show that organically produced food has less residues from pesticides than conventionally produced food [7]. However, pesticides are allowed in organic farm practices. For example in Switzerland there is a 123 pages document that lists all allowed pesticides, fertilizer, anti-parasite agents and cleaning detergents that are allowed [8]. Most organic pesticides are natural toxins such as vegetable oils, hot ash soap, sulfur or copper sulfates but some synthetics as well. Organic pesticides are not safer than their synthetic counterparts [9] in the end both are toxic. As a matter of fact, in the case of copper sulfate which is often used as a pesticide on organic apples, it can cause severe harmful effects to human health and is of ecotoxicological concern due to toxicity to aquatic organisms [10].

Health

A handful of studies found that organic foods contain more antioxidants and more vitamins which proposedly has health benefits [11] . Overall study results regarding the health benefits of organic food are still mixed and further research has to be done. In general, one can say that there are not significant differences in nutritional values [12].

Ethics and Environment

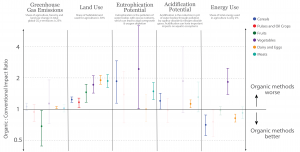

In 2017 Clark & Tilman conducted a meta-analysis on environmental impact factors and compared organic food with regular food from over 700 production sources. The categories were greenhouse gas emissions, energy consumption and land needs. They found that no production method is clearly better for the environment. Organic systems use less energy than conventional ones but have similar greenhouse gas emissions. Organic farms also use less pesticides but in contrast they need much more land to produce the same amount of crop [13]. These mixed results were also confirmed by the Swedish Food agency. The study confirmed these results and showed that conventional and organic farming production were mostly equal except in pesticides, where organic farming has less impact and land use where conventional farming has a much lower impact so that overall conventional farming has a little bit less impact on the environment [14]

Figure 1 The relative environmental impact of organic and conventional agriculture across various ecological and resource indicators based on [13] Metrics are presented as the ratio of impacts from organic methods to conventional farming methods: Impact ratios higher than 1 indicate larger environmental impacts from organic methods, and > 1 indicate smaller impacts. Picture Source [15]

The ethical part is much harder to quantify. A multitude of factors lead into this aspect e.g. working conditions, animal welfare, biodiversity. Overall, it can be said that farms that live up to the principles of organic farming give their animals the opportunity to live more natural lives as well as increased possibilities for sufficient human care [16]. Organic farming shows also increased biodiversity of plant and animal species on the farm, an important factor for sustainability. Hole et al. found that the majority of their farms studied indicated an increase in species abundance, richness, and activity compared to conventional counterparts [17]. Berbec et al. did a comparison of the sustainability performance of organic and low-input conventional farms in Eastern Poland. They assessed factors according to the RISE indicator system (e.g. biodiversity, working conditions, quality of life etc.). They came to the conclusion that the systems performed relatively equally. Organic farms showed higher performance in biodiversity whereas low-input conventional farms had better economic viability [18].

Now what?

I hope it became evident by just barely scratching the surface of this topic, that this is a very multifaceted, complex and sometimes ambiguous subject. Certainly more complex than the slider option question of “I make sure that most of what I consume is bio and organic.” There is a danger in consuming just on an ideology without questioning whether it is actually the better option. As ETH students and affiliates, I believe it is our duty to critically question it. I am aware this blog cannot answer what is the best option for your specific situation, as you would need LCAs for all the individual cases. However, while researching this topic some points became evident to me. First, you have to be clear about your intentions why you want to consume bio based on your individual value system. For example, if you are mostly concerned about animal welfare then bio is clearly the better choice. When you buy vegetables or fruit, animal welfare is not an issue anymore, your value system changes. Let’s assume you are then mostly concerned about environmental impact. Then the problem becomes much more complicated and simply buying organic is not the answer. For instance off season vegetables produced in greenhouses have abysmal CO2 balances regardless of how they were produced. If you consume locally produced asparagus in March (produced in greenhouses) they have a CO2 footprint of 5kg CO2 / kg. As a comparison avocado imported by ship from Peru during the same time have a footprint of 1.4 kg [19]. Whether or not these avocados have been produced organically or conventionally is neglectable in terms of environmental impact as seen in figure 1.

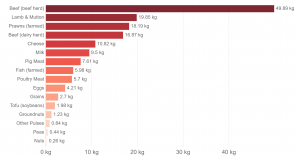

Therefore, I really want to stress that it is much more important what you consume compared to in what agricultural system it was produced. If you have chosen to forego your bio beef meat and replace your protein consumption with conventionally produced nuts obviously that is a much better choice for the environment regardless of the production method as seen in figure 2.

Figure 2 Comparison of greenhouse gas emissions in kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalents (kgCO2eq) per 100 grams of protein. This means non-CO2 greenhouse gases are included and weighted by their relative warming impact [15].

Figure 2 Comparison of greenhouse gas emissions in kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalents (kgCO2eq) per 100 grams of protein. This means non-CO2 greenhouse gases are included and weighted by their relative warming impact [15].

Let’s assume another case where you have the choice between two Swiss apples, one organically produced the other conventionally. According to Clark and Tilman [13] conventional has a slight edge in terms of environmental impact. However, the difference is minute so that the effects could be offset by the retailer’s storage and transport methods. This also shows that more transparency and information that is available to the consumer is needed. I encourage all of you to look very closely into what you consume and why you consume it.

Bibliography

| [1] | International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements, “The IFOAM NORMS for Organic Production and Processing Version 2014,” IFOAM, Bonn, 2014. |

| [2] | European Union, “Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 on organic production and labelling of organic products and repealing Regulation,” EEC, Luxemburg, 2007 . |

| [3] | Cornell Law School, “7 CFR Subpart C – Organic Production and Handling Requirements,” Cornell, 2018. |

| [4] | FAO, “Organic agriculture FAQ, What is organic agriculture?,” 2018. [Online]. Available: http://www.fao.org/organicag/oa-faq/oa-faq1/en/. [Accessed 17 4 2020]. |

| [5] | J. Baudry, “Food Choice Motives When Purchasing in Organic and Conventional Consumer Clusters: Focus on Sustainable Concerns (The NutriNet-Santé Cohort Study),” Nutrients, vol. 2, no. 9, p. 88, 2017. |

| [6] | B. B, “Sustainable Diets and Biodiversity—Directions and Solutions for Policy Research and Action Proceedings of the International Scientific Symposium Biodiversity and Sustainable Diets United against Hunger.,” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 2012. |

| [7] | European Union, “The 2015 European Union report on pesticide residues in food, 2015,” European Food Safety Authority, Brussels, 2015. |

| [8] | FiBL Schweiz, “Betriebsmittelliste für den biologischen Landbau in der Schweiz,” FiBL, Frick, 2020. |

| [9] | University of Illinois, “Going organic: Are organic pesticides safer than their synthetic counterparts?,” University of Illinois Extension, 2 June 2017. [Online]. Available: https://aces.illinois.edu/news/going-organic-are-organic-pesticides-safer-their-synthetic-counterparts. [Accessed 17 04 2020]. |

| [10] | A. Mie, “Human health implications of organic food and organic agriculture: a comprehensive review,” Environmental Health, vol. 16, no. 111, p. 111, 2017. |

| [11] | R. B, “Nutritional quality of organic foods: a systematic review,” Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education, vol. 7, p. 532, 2017. |

| [12] | D. AD, “Nutritional quality of organic foods: a systematic review,” The American Journal of clinical nutrition, vol. 3, no. 90, p. 680, 2009. |

| [13] | C. &. Tilman, “Comparative analysis of environmental impacts of agricultural production systems, agricultural input efficiency, and food choice.,” Environmental Research Letters, vol. 12, no. 6, 2017. |

| [14] | B. Landquist, “Litteraturstudie av miljöpåverkan från konventionellt och ekologiskt producerade livsmedel,” Livsmedelsverket National Food Agency, Sweden, 2016. |

| [15] | H. Ritchie, “Is organic really better for the environment than conventional agriculture?,” University of Oxford, Oxford, 2017. |

| [16] | M. V. &. h. Alroe, “Concepts of Animal Health and Welfare in Organic Livestock Systems,” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, vol. 25, pp. 33-347, 2011. |

| [17] | D. Hole, “Does organic farming benefit biodiversity?,” Biological Conservation, vol. 122, no. 1, pp. 113-130, 2005. |

| [18] | A. Berbec, “Assessing the Sustainability Performance of Organic and Low-Input Conventional Farms from Eastern Poland with the RISE Indicator System,” Sustainability, vol. 10, 2018. |

| [19] | A. Wiedmer, “Weltweit saisonal,” Gebana, 15 11 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.gebana.com/de/blog/2019/11/15/weltweit-saisonal/?utm_source=CleverReach&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=13-11-2019+NL+CH+15.11.2019+Wann+importieren%3F+&utm_content=Mailing_13496662?utm_source=CleverReach&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=13-11-2019. [Accessed 19 04 2020]. |

Media Attributions

- Organic-vs.-Conventional-Impacts-FINAL-01 (2)

- ghg-per-protein-poore (2)