Ambra Giorgetti

Imposed quarantine is probably the most efficacious weapon we have at the moment to contrast the incessant diffusion of the coronavirus infection. The ability of the population to cope with the new conditions might depend on various factors, such as previous experiences, education, socio-economic status and perceived threaten. As with every big-scale intervention, there are side effects that must be considered and strategies to counteract the negative consequences that must be planned.

Every cloud has a silver lining – what I learned from 4 months in a rural village in Kenya

I am among the lucky scientists who can conduct part of their research in the field. Most of my projects are based in a remote village in the south of Kenya and I spend approximately one third of my year in rural settings. In such context, the challenges that need to be faced daily are many, ranging from the adaptation to a different environment to changes in your personal routine. Before leaving Europe for the first time, I tried to picture in my mind what adjustments would have been needed to successfully adapt to the new situation. In general, I am a very dynamic person who loves the possibility of going anywhere at any time without feeling threatened. I never took this freedom for granted and I knew in advance that there would be some restrictions, but I never imagined how stressful it turned out for me to conduct most of my daily activities in the same place (the study house). Living in the village means that almost all your movements needs to plan in agreement with a driver. There are no offices, no sport facilities, no libraries, no shop and most of your food can be bought in the close neighborhood of your house. Adapting to this new situation was far from easy. At the beginning my work productivity, as well as my motivation in all the other activities, such as training, were reduced dramatically. I got bored and I felt oppressed from seeing the same surroundings all day long. I decided to search online for some inputs supporting me in arranging my time and space in a more efficient way. The strategy I decided to adopt was to confine spatially all my activities to different rooms and to move away from that specific place once the activity was completed or the productivity decreased. For example, I assigned a definite location in the living room to my PC and I only sat there while working. Whenever I needed a break, I moved to another room in the house or I went for a small work in the garden. This approach helped me adapting to the situation and I started seeing small but constant rise in my productivity and motivation. However, I must admit that what helped me the most was being more indulgent with myself. I learned to accept that it takes time to metabolize variations of your routine. I started learning that punishing myself for not being a great performer is detrimental. I started accepting the whole adaptation process and I tried not to feel guilty for not being as efficient as before. From my personal experience, this was the only way possible to start getting closer to my usual standards.

I was in the field when I was hit by the first news about the massive and quick spread of the novel coronavirus in the Hubei area. My collaborators and I were constantly looking at the numbers of infected and recovered people rising exponentially day after day. Within a few weeks, travel restrictions, widespread lock down and borders closure had caught most of the people worldwide in a modern form of quarantine. I managed to fly back to my country and I realized how quickly the familiar environments and habits I was used to had changed in three months. In order to slow down the rate of infection and to prevent a dramatic degeneration in the global health status, people were (and still are) asked to stay home and to limit the movements to the essential ones. This translates into a single place, i.e. the house, where all the daily activities are performed. Unsurprisingly for me, many of my friends and colleagues faced the exact same difficulties I experienced during my first trip to Kenya. I tried my best to learn from my experience and to find a way to cope with the situation. I noticed that I was among the ones better reacting to all the sudden changes. However, I quickly realized that, in addition to the restrictions, most people are trying to cope additional layers of economic and social insecurity.

A new challenge to be faced

The lock downs have led to a collapse of the global economy, vaporizing more millions of jobs in just two weeks. In the US only, nearly 10 million people applied for unemployment benefits in the past two weeks. A great majority of employers and entrepreneurs have seen their salary transfer being postponed and/or their income consistently reduced. Many governments are designing schemes of unemployment benefits for workers and financial aids for companies, but this will likely take a few weeks or months to be applied. Furthermore, not all citizens in need might be able to benefit from these measures or they might be already struggling with covering the essential living costs. In addition, the scientific community is facing an unknown pandemic for the first time in recent history. Teams of scientists are offering their specific knowledge to governmental institutions to support decisions aiming at containing the infection. However, a multitude of questions about the etiology of the disease, the way it spreads and which treatment might be effective in infected patients remain unsolved. Given all these variables, it is hard to predict when the lock down will end and which approach will be used to suspend the restrictions.

The combination of undefined quarantine, social distance, financial instability and uncertainty of the future might produce a pandemic of fear unfolding alongside the pandemic of the coronavirus. Fear contagion seems to spread even faster than the dangerous yet invisible virus. Media announce mass cancellations of public events over coronavirus fears; TV stations show images of coronavirus panic shopping. All these inputs triggered my thought about the short- and long-term consequences of the widespread lock down. I concluded that, regardless of whether it succeeds in controlling the outbreak and preserving our physical health, the extensive lock down is having and will inevitably have a massive psychological effect on the world population.

Coronavirus: the indirect effects of quarantining the world

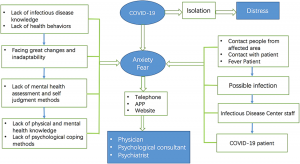

According to the World Health Organization Constitution, “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity […] Governments have a responsibility for the health of their peoples which can be fulfilled only by the provision of adequate health and social measures”. I certainly realize that humankind is facing the biggest crisis of the last 50 years. I am aware that the priority now is to overcome the immediate treat and I understand why focus is placed on economy and healthcare. However, the preservation of the well-being of the population is of utmost importance. My fear is that the consequences of the pandemic itself and of the restrictions adopted to tackle it on the mental health of the population are not properly undertaken. To examine more in depth this idea, I started looking for evidence from the coronavirus pandemic and related emergencies from the past. My goal was to examine the actual psychological response of the population from countries adopting the lock down. Furthermore, I was curious about the outcomes arisen from similar approaches in previous outbreaks, such as the SARS. Concerning the first point, I discovered there are recent studies highlighting the need of urgently delivering mental health support to patients, health workers, but also to people suffering from preceding mental disorders. Moreover, other studies recommend guaranteeing psychological support for the general population as well. In fact, “the outbreak itself and the control measures may lead to widespread fear and panic, especially stigmatization and social exclusion of confirmed patients, survivors and relations, which may escalate into further negative psychological reactions including adjustment disorder and depression” (Figure 1).

Figure 29.1 – Figure 1: The emotion hypothetical model of psychological crisis intervention in COVID-19 epidemic. Precision Clinical Medicine, Volume 3, Issue 1, March 2020, Pages 3–8, https://doi.org/10.1093/pcmedi/pbaa006

However, so far, according to a paper published in “The Lancet Psychology”, “mental health care for the patients and health professionals directly affected by the 2019-nCoV epidemic has been under-addressed, although the National Health Commission of China released the notification of basic principles for emergency psychological crisis interventions for the 2019-nCoV pneumonia on January 26, 2020”. A reason for that might be the lack of epidemiological data on the mental health problems and psychiatric morbidity of those suspected or diagnosed with the 2019-nCoV after the recovery, their close relatives and health professionals. In addition to this, since the virus outbreak is at the crucial point and only a few countries have started loosening their restrictions, it is unreasonable to expect now indicators assessing the long-term effects of the measurements. Nevertheless, examples from which we can learn exist, and they include, among others, the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the SARS influenza and the recent Ebola virus outbreak in 2013. In these situations, the consequences on the psycho-social well being of the whole populations were largely overlooked, and little effort was made to address the mental health needs of confirmed patients, their families, medical staffs or general population. This resulted into an increased risk of psychological distress and progression to psychopathology, which added to the already week health care system especially in developing countries, such as Sierra Leone. In addition to the fear and anxiety arising in the general population from the disease outbreak, T. Canli in his paper published on BMC speculates about plausible psychological pathways by which parasitic, bacterial, or viral infections might contribute to the development of major depression. He points out that the symptoms of major depression resemble the ones from pathogenic infection and this is further confirmed by post-mortem studies reporting the presence of inflammatory markers in the brains of depressed or mood-disordered patients. Lastly, some examples in animal species exist about parasite infections affecting specific functional mechanisms in the nervous system, which lead to changes in emotional behavior.

Some organizations, such as Save The Children, or local associations of psychologists offer support assisting the population with free online counselling if requested. Nevertheless, regardless of all this scientific evidence supporting the potential impact of the outbreak on mental and psycho social well-being, I was unable to find measures and strategies addressing this issue coming from governments or similar institutions.

Conclusion

Worldwide, different countries have experienced various degrees of severity of coronavirus infections and death rate. One of the predominant factors accounting to these differences is the rate of exposure to undetected cases and the inability to confine spatially the new disease outbreaks. However, after the detection of the first cases, some countries were able to tackle the emergency better than others were. The speed and efficacy in preserving the physical health of the population of the restrictive measurements were proportional to the level of previous experience with similar illnesses (such as South Korea and SARS) and to the accessibility to structured health care facilities. However, the strongest limitation to the efficacy of any approach is the huge amount of unsolved questions we still have about the disease origin, transmission and development.

When it comes to mental health, we have indications of how the emergency might affect our psychological state from past epidemic. Although the virus aetiology is yet to be defined, the advantage in this context is that the approach used in the past to prevent the spread of the infection is the same as the one adopted currently worldwide. Therefore, the consequences on mental health are expected to be similar. My conclusion is that, in addition to the development and implementation of economic and health measurements, mental health assessment, support, treatment, and services should be acknowledged as crucial and pressing goals for the health response to the 2019-nCoV outbreak.

https://academic.oup.com/pcm/article/3/1/3/5739969

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-0366(20)30046-8/fulltext

https://biolmoodanxietydisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2045-5380-4-10

https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/01/24/coronavirus-the-psychological-effects-of-quarantining-a-city/

Media Attributions

- Picture1