Tse Huang

As the world and urban population continue to grow, there will be increasing demand on the urban infrastructure for essential services such as electricity, sanitation, and safe drinking water. To support improvements in essential services and other key factors in making less developed cities more sustainable, it is necessary to learn from past mistakes and retain high-skilled workers.

Why the focus on cities?

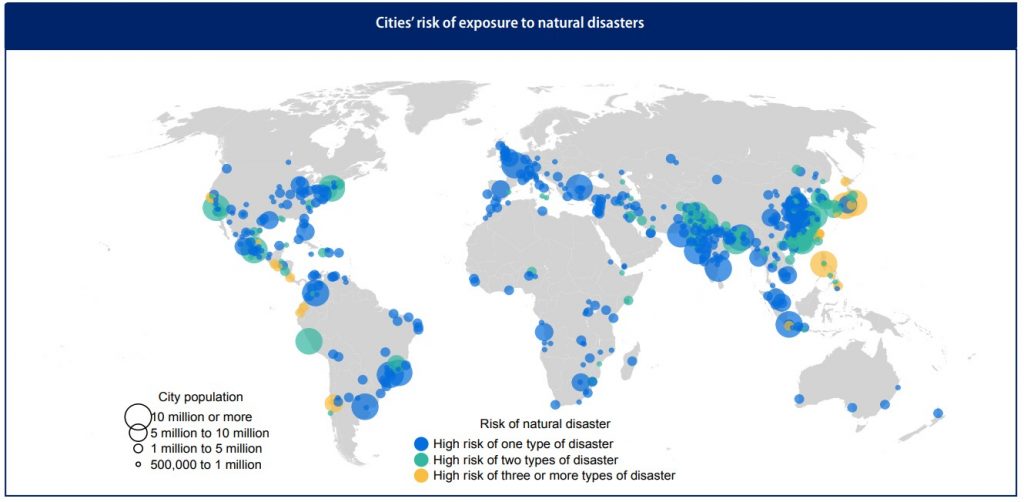

Many cities around the world are currently facing challenges in managing the rapid inflow of people into urban areas. This results in the need to increase housing supply, infrastructure capacity, and resiliency to disasters to only name a few 1. The dangers cannot be underestimated since even as recently as 2016, 91% of people in urban areas worldwide did not have access to minimum clean air quality as defined by the World Health Organization. This poor air quality contributed to an estimated 4.2 million deaths 6. As of 2018, nearly 60% of all cities with at least 500 thousand inhabitants are at high risk of at least 1 type of natural disaster with up to 1.4 billion lives at risk 5.

Figure 81.1 – Cities at risk of exposure to natural disasters

The problem is only going to increase as the world population continues to migrate to urban areas. Already in 2018, 55% of the world population live in urban settlements and this number is expected to increase to 70% by 2050. This large concentration of people requires significant concentration of effort as cities account for 65% of the total sustainable development goals (SDG) targets and 86% of all SDG indicators 1. Therefore, directing our focus on cities as soon as possible will have long term positive impacts for a large proportion of people all over the world.

What makes a good (sustainable) city?

The philosopher Confucius once said that a good city is one that “keeps the local citizens happy and attracts people from afar” and I would argue that it has not changed today. There are many rankings for top “most livable cities” all over the internet today and these rankings come with many different indicators and unique approaches to evaluating cities but they all have common metrics that are consistent with SDG 11 for cities; inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. SDG 11 further breaks this down into several key factors which include the following 1:

- Safe and affordable housing and basic services

- Safe, sustainable transport systems

- Inclusive urbanisation and participatory, integrated planning

- Cultural and natural heritage

- Resilience to distances

- Reduced environmental impacts

- Green and public spaces

All of these factors are important to people’s quality of life and is part of their consideration in choosing where to live and work. To achieve the overall goal in making a city sustainable though is no small feat and will require significant investment since as of 2015, an estimated 75% of global infrastructure that will exist in 2050 has not even been built yet 1.

Figure 81.2 – Aerial view of park in a city

Learning from past mistakes

Existing large cities have historically struggled with balancing environmental considerations and quality of life with economic development. This resulted in large scale problems with costly solutions. For instance, many developed nations did not even have policies and laws to protect water quality in the urban environment until recently (1987 in the USA, 1998 in the EU, 1994 in Australia). These policies could not immediately change water quality though since the existing infrastructure for many cities was already constructed, could not be feasibly modified to meet the new regulations, and ultimately require expensive replacement once they reached their design lifespan. An example of this past mistake being painfully corrected now is in New York City where they initiated a green infrastructure plan in 2010 to reduce their combined storm and sewage waste by 50% with infrastructure upgrades totaling 5.3 billion USD over 20 years. Much of this cost attributed to the replacement of non-compliant infrastructure constructed before the stringent environmental policies were introduced. The “green” part of the plan refers to new nature-based techniques in managing stormwater and it is projected to save 1.5 billion USD when comparing the level of performance with equivalent traditional “grey” infrastructure 7.

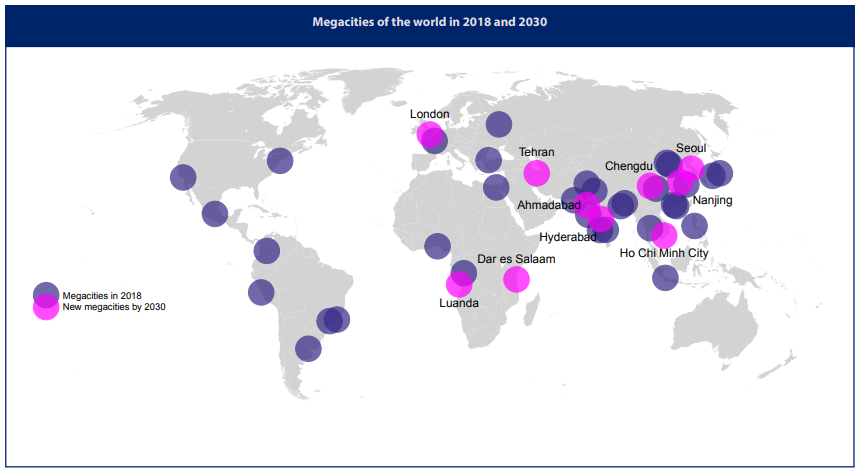

Other examples include an insufficient supply of affordable housing, the need to procure expensive land in expanding the transport system, and inefficient building stock throughout the city. Most cities did not historically place emphasis on access to public spaces. A study on 220 cities in 77 different countries from 2018 indicates that only 21% of people had convenient access to public spaces and their distribution is uneven 6. However, most megacities of the world in 2030 are predicted to be located in currently less developed regions 5. These cities, as well as newer and future cities, have the opportunity to learn from the mistakes of the past since they have more flexibility in the choice of future investments. With SDG 11 in mind, cities should strive to invest deliberately and strategically in public transport, enforce regulations for efficient buildings allocate sufficient area for green spaces, and construct nature-based water management systems where possible.

Figure 81.3 – Location of Megacities in 2018 and 2030

Where is the source of investment for urban infrastructure?

The main instrument available for infrastructure investment is through debt financing or other loans to be paid back over time through user fees and/or taxation of the population. Investment in infrastructure is a global challenge with a distinct gap in developing countries. Cities need to demonstrate the ability to provide sufficient returns on the initial investments from a growing population base as well as high levels of income per capita. Cities in high-income countries have an advantage in the ability to obtain debt financing through their high international credit ratings (low risk) for infrastructure projects. Meanwhile, cities in middle and low-income countries are typically considered too high risk for investment and often need to rely on more limited financing from multilateral development banks such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the World Bank’s Global Infrastructure Facility 2.

Why the competition for high-skill workers?

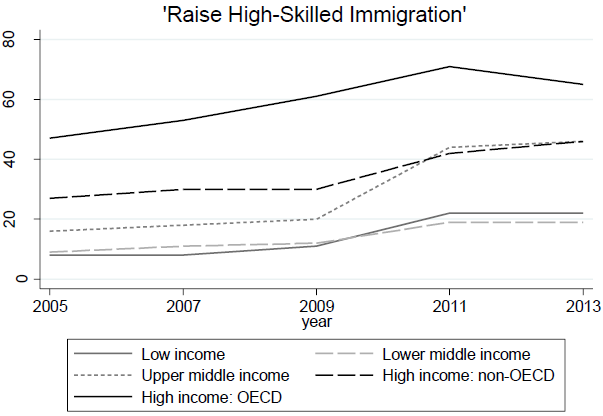

High-skilled workers are vital resources for cities since they contribute a disproportionate amount of revenue for cities by typically spending more on goods and services, own property, and contribute a higher percentage of income tax. More revenue for cities will ultimately increase their ability to raise capital for necessary sustainable infrastructure projects. However, high-skilled workers are limited in supply and require years of education to develop. They are also four times more likely to migrate than low-skilled workers and results in significant positive impacts for the receiving city 3. Migration may be within a country as competition between cities or internationally to different countries. Countries all over the world are discovering a shortfall of domestic supply in high skilled workers and in recent years revised their immigration policies to favor high-skilled migrants 4.

Figure 81.4 – Government policy objectives on high-skilled migration, (% of countries)

What can be done to ensure cities are competitive in retaining talent?

People do not only value economic incentives in making their decision on where to live. Many of the important factors they also consider are defined in the goals of SDG 11 for sustainable cities such as safety, good transport, affordable housing, culture, and inclusivity. An excellent strategy to keep people engaged in the path to becoming a sustainable city is through a participatory planning process where experts and locals share their knowledge and concerns on new proposed projects in their communities. Local participation produces more robust designs and decisions since they have the opportunity to voice their needs, it demonstrates transparency in the project with professionals sharing the time, budget, and technical constraints 8.

Figure 81.5 – Infographic showing the combined knowledge obtained from participatory planning process

Habitations Émile-Nelligan II in Montreal is an example of how the participatory planning process can deliver results and empower the local community at the same time. It is a social housing project designed to reduce the heat island effect in the neighborhood back in 2010. Local residents were asked to participate in the landscape design of the improvements through workshops lead by professionals where they voiced their needs and reviewed preliminary designs that were developed based on their input. The final design was then executed and constructed into a new green space that improved their daily lives and the city overall 8.

Figure 81.6 – Before [left] and after [right] images of the Habitations Émile-Nelligan II housing project in Montreal

Many countries have taken notice of the importance of their cities in ensuring prosperity for their people in the future since cities already contribute to over 80 % of global gross domestic product (GDP). As of 2019, 150 countries have developed national urban policies to specifically respond the to challenges described here and almost 50% have started putting these policies into action 6.

The path to sustainable cities is not quick but people will need to see real progress over the coming years towards this sustainable development goal. They need to see that their governments are taking active steps in improving the situation in their cities and have an opportunity to contribute by participating in the process. If not, those who can, will vote with their feet and relocate somewhere else that does better a better job. For many though, home is hard if not impossible to replace and if your home community is truly progressing towards a sustainable future then it is sure to not only keep you happy but also attract people from afar.

References

(1) UNEP. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://wedocs.unep.org/: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/25763/SDG11_Brief.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

(2) COALITION FOR URBAN TRANSITIONS. (n.d.). newclimateeconomy. Retrieved from https://newclimateeconomy.report/workingpapers/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2018/01/NCE2017_CUT_GlobalReview_02012018.pdf

(3) Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration. (n.d.). cream-migration.org. Retrieved from https://www.cream-migration.org/publ_uploads/CDP_24_16.pdf

(4) Mathias Czaika, C. P. (2015, June 07). https://voxeu.org/. Retrieved from https://voxeu.org/article/attracting-high-skilled-migrants

(5) United Nations. (2018). un.org. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/events/citiesday/assets/pdf/the_worlds_cities_in_2018_data_booklet.pdf

(6) United Nations. (2020). sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg11

(7) Ni-BinChang, J.-W. T. (2017). Global policy analysis of low impact development for stormwater management in urban regions. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.11.024

(8) Montréal Urban Ecology Centre. (2015). participatoryplanning.ca. Retrieved from https://participatoryplanning.ca/sites/default/files/upload/document/participatory_urban_planning_brochure_2016.pdf