Amélia Graber

Zurich’s mobility system has been doing well on various indices such as the HERE urban mobility index and the Omio technical report on Inner-City Mobility in European Cities that both ranked the city first in 2018 and 2019 respectively. This is the result of a transportation system continuously improved by the Zurich’s government and is mostly due to well-functioning public transport (Menendez & Ambühl, 2022) . Yet the city’s mobility system is negatively affecting the health of a third of its residents because of another means of transport: cars (Cucurachi et al., 2019; Stadt Zürich, n.d.-c). In the following text I want to focus on how the noise cars make impacts the health of Zurich’s population and what could or should be done about it.

Figure 1 Traffic in front of the Kunsthaus in the centre of Zurich

Zurich and its cars

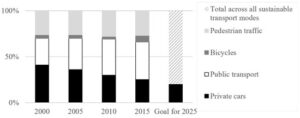

Despite Zurich’s efficient public transport system cars represent an important part of the city’s mobility system and impact its population’s health through noise emission. As shown in figure 2 the modal share of cars has decreased over the past two decades whereas public transport has steadily increased (Menendez & Ambühl, 2022). Being used at least twice a week by 22% of Zurich’s population, cars represent a non-negligible transportation vehicle even so (Dorbrit, 2020). Especially considering that motorized vehicles are the biggest generator of noise in the city and contribute to 105’000 people being exposed to noise levels above the legal limit (Cucurachi et al., 2019; Stadt Zürich, n.d.-a, n.d.-c). Set in 1983, the limit is still far from being reached (Jordi, 2005). One of the measures taken to reduce the damaging noise levels was to introduce low-speed areas (30km/h), the first being established in 1991. A few have followed since, freeing 24’000 people by 2020 of excessive noise (Menendez & Ambühl, 2022; Stadt Zürich, 2021). Other implemented measures, aiming at making alternatives to cars more attractive, include prioritizing pedestrians in the city centre and the Masterplan Velo, which pursues better cycling infrastructure (Menendez & Ambühl, 2022).

Figure 2: Modal share of different means of transport over time in Zurich (Menendez & Ambühl, 2022)

The impact of traffic noise on health

According to the WHO noise results in more than a million DALY’s[1] being lost in western Europe every year (Fritschi et al., 2011). Exposure to noise can lead to sleep disorders and stress reactions in the body which in turn can cause heart diseases, diabetes and cognitive impairment of children (Röösli et al., 2019). Additionally, noise can impact individuals psychologically: a study showed that “a higher proportion of those who lived in the noisy area in apartments with windows facing the street more often felt depressed [while] those who had windows facing the courtyard, in the noisy area, […] were not more depressed than those who lived in the quiet area” (Öhrström, 1991). In general, having access to quiet indoor and outdoor areas is an important component of psychological and physiological well being (Öhrström et al., 2006).

Measures: Past – present – future

In the following paragraph I am going to touch on four ways in which Zurich could tackle the traffic noise problem and measures already taken.

One way to reduce the noise traffic causes is to lower the speed limit. It is an effective and cheap way to tackle the problem at its source and can lead (for speeds being lowered from 50km/h to 30km/h) to a reduction of 2 dB to 4.5 dB depending on effective speed, truck percentage and pavement (Bühlmann et al., 2017). As mentioned above, Zurich has been introducing areas with a maximal speed of 30 km/h (“Tempo 30”) since 1991 and is planning on adding many new ones until 2030 to solve its noise problem. The city wants to complement this measure with low-noise pavements when necessary (Stadt Zürich, n.d.-b).

Another way Zurich is trying to reduce the effect of traffic noise on its residents is by changing the mobility infrastructure. There is currently an underpass being built for cars in Schwamendingen aiming at lowering noise- and airpollution and reconnecting neighbourhoods previously separated by a large street (Stadt Zürich, n.d.-b). An example of a failed project is the underground tunnel at the Rosengartenstrasse known for being the loudest street in Switzerland, which highlights a big disadvantage of this measure: its price. The billion franks project was rejected in a vote by 60% of the population and it is now planned to introduce a low-speed zone (Brandenberger, 2021; SRF, 2020).

Electric and hybrid cars can also lead to a reduction of traffic noise. If their share rises to around 90% the noise level drops by 3 dB to 4 dB. While this method achieves a noise reduction comparable to that of a lower speed, there is still a long way to go before we reach a share of 90 % of electric and hybrid cars (Jabben et al., n.d.).

Lastly, the amount of cars driving through Zurich could be reduced. Different measures such as “limiting (or even completely avoiding) the expansion of the car traffic network, limiting parking, and implementing other car restricting policies” could lead car users to choose less noisy and more sustainable options (Menendez & Ambühl, 2022). While the high parking price in Zurich supports the city’s aim at prioritizing other means of transport the increasing number of available parking counteracts this effect. Fortunately, the city does have the attractive alternative of public transport and is prioritizing cyclists and pedestrians in the inner city which makes it easier for car users to switch to alternatives (Menendez & Ambühl, 2022; Stadt Zürich, n.d.-d). The extreme end of reducing cars would be to go car free, which other cities such as Hamburg, Helsinki, Madrid and Oslo have announced they would partly implement (M. J. Nieuwenhuijsen & Khreis, 2016). A major concern is often that such measures could negatively affect retail but similar measures in Germany have shown no negative effect (M. Nieuwenhuijsen et al., 2018). Nevertheless, it could be “a catalyst for better town planning by removing the need to facilitate car mobility and ensuring that urban areas are planned around people, functionality and better built environments instead” (M. Nieuwenhuijsen et al., 2018).

Conclusion

Altogether it is clear that Zurich’s mobility system is constantly being improved and that it has certain well-designed aspects such as its efficient public transport system. However, especially considering the current ecological crisis it is worrying to see that the city has been unable to adjust its mobility system to laws passed in 1983 to protect the health of its residents. While Zurich prioritises pedestrians, bikes and public transport it doesn’t actually prioritize its citizens when planning mobility measures. It accepts impairing the life of a third of its population over introducing more effective measures on a larger scale. All measures discussed above could be more widely implemented and would thus reduce the negative effect of traffic noise on Zurich’s citizens. Lastly, deprioritizing cars represents an opportunity to resolve many other problems they generate regarding sustainability such as air pollution, CO2-emissions and traffic accidents.

References

Brandenberger, J. (2021, December 19). Tempo 30 in der Stadt Zürich – Kampf um die Rosengartenstrasse. SRF. https://www.srf.ch/news/schweiz/tempo-30-in-der-stadt-zuerich-kampf-um-die-rosengartenstrasse

Bühlmann, E., Egger, S., Hammer, E., & Ziegler, T. (2017). Basic information for assessing noise effects at speed limit 30 km/h Noise reduction potential of speed limit 30 km/h View project Effective noise abatement through quieter tyres View project. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318394334

Cucurachi, S., Schiess, S., Froemelt, A., & Hellweg, S. (2019). Noise footprint from personal land-based mobility. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 23(5), 1028–1038. https://doi.org/10.1111/JIEC.12837

Wikipedia. (2022). Disability-adjusted life year. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disability-adjusted_life_year

Dorbrit, R. (2020, June 3). Kennzahlen der Verkehrsentwicklung. https://www.stadt-zuerich.ch/ted/de/index/taz/verkehr/webartikel/webartikel_kennzahlen_verkehrsentwicklung.html

Fritschi, L., Brown, L., Kim, R., Schwela, D., & Kephalopolous, S. (2011). Burden of disease from environmental noise Quantification of healthy life years lost in Europe. http://www.who.int/quantifying_ehimpacts/publications/e94888/en/

Jabben, J., Verheijen, E., & Potma, C. (n.d.). Noise reduction by electric vehicles in the Netherlands.

Jordi, B. (2005). Auf der Suche nach der verlorenen Ruhe. Umwelt, 6–9.

Menendez, M., & Ambühl, L. (2022). Implementing Design and Operational Measures for Sustainable Mobility: Lessons from Zurich. Sustainability 2022, Vol. 14, Page 625, 14(2), 625. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU14020625

Nieuwenhuijsen, M., Bastiaanssen, J., Sersli, S., Waygood, E. O. D., & Khreis, H. (2018). Implementing car-free cities: Rationale, requirements, barriers and facilitators. Integrating Human Health into Urban and Transport Planning: A Framework, 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74983-9_11/FIGURES/2

Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., & Khreis, H. (2016). Car free cities: Pathway to healthy urban living. Environment International, 94, 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENVINT.2016.05.032

Öhrström, E. (1991). Psycho-social effects of traffic noise exposure. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 151(3), 513–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-460X(91)90551-T

Öhrström, E., Skånberg, A., Svensson, H., & Gidlöf-Gunnarsson, A. (2006). Effects of road traffic noise and the benefit of access to quietness. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 295(1–2), 40–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSV.2005.11.034

Röösli, M., Wunderli, J.-M., Brink, M., Cajochen, C., & Probst-Hensch, N. (2019). Die SiRENE-Studie. Swiss Medical Forum ‒ Schweizerisches Medizin-Forum. https://doi.org/10.4414/SMF.2019.03433

SRF. (2020, February 9). Kanton Zürich – Stimmvolk stoppt Milliardentunnel. https://www.srf.ch/news/schweiz/abstimmungen-oberrubrik/abstimmungen/kanton-zuerich-stimmvolk-stoppt-milliardentunnel

Stadt Zürich. (n.d.-a). Mehr Schutz vor Lärm durch weitgehende Einführung von Tempo 30. Retrieved April 11, 2022, from https://www.stadt-zuerich.ch/pd/de/index/das_departement/medien/medienmitteilung/2021/juli/210714a.html?msclkid=8f421f1fb4ec11ec99c257c419083772

Stadt Zürich. (n.d.-b). Strassenlärmsanierung. Retrieved April 11, 2022, from https://www.stadt-zuerich.ch/ted/de/index/stadtverkehr2025/strassenlaermsanierung.html

Stadt Zürich. (n.d.-c). Strassenverkehrslärm. Retrieved April 11, 2022, from https://www.stadt-zuerich.ch/gud/de/index/gesundheitsschutz/schadstoffe_laerm_strahlen/aussenraum/laerm/strassenlaerm.html

Stadt Zürich. (n.d.-d). Velostrategie 2030. Retrieved April 11, 2022, from https://www.stadt-zuerich.ch/ted/de/index/stadtverkehr2025/velostrategie_2030.html

Stadt Zürich. (2021). Stadtverkehr 2025. www.stadt-zuerich.ch/stadtverkehr2025

- "The disability-adjusted life year (DALY) is a measure of overall disease burden, expressed as the number of years lost due to ill-health, disability or early death." (Wikipedia, 2022) ↵