Mona Gairing

Care work is still not recognized enough in public perception. Care work – traditionally women’s responsibilities – is, like nature, too unimportant to mention. Even though the careful management of habitats, people and their communities must become the overriding political and economic principle. (Nelson, 2009; Ringger, 2019)

The Non-Monetized Half of the Cake

According to Julie Nelson (2009) share women and nature a similar treatment in neoclassical economics. She describes the parallels as follows: “They are variously, invisible, pushed into the background, treated as resources for the satisfaction of male or human needs, considered to be part of a realm that “takes care of itself”, thought of as self-regenerating, conceived of as passive, and/or considered to be subject to male or human authority”.

Mainstream economy only focuses on the explanation of competitive production and exchange in markets. This theory is too simplistic to adequately explain economy. There is no way to integrate the topic of children and care work into this model. There is also the assumption that a productivity increase is possible everywhere or more productive activities can replace less productive ones and that there is a separation between worker and product. In the “other economy” which deals with the direct production and maintenance of people as an end in itself, is hardly any increase in production possible and the relationship between the caregiver and the cared-for person is essential. (Donath, 2010)

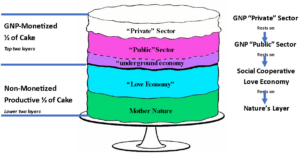

The alleged irrelevance of care work and nature is also reflected in the way that people measure the health of an economy and the well-being of a nation. Traditionally the GDP is used. Environmental activists and feminist economists though claim that it is not a good measurement of the well-being of a nation. It for example does not include clean air, beautiful forests, family, volunteer work, traditionally feminine unpaid work, and many other unmonetary contributions to society. Hazel Henderson, a futurist and evolutionary economist, uses the metaphor of a layered cake (see Figure 1) to illustrate how the GDP ignores important contributions that social love economy, such as traditionally feminine work, and mother nature make to a society. Traditional economics focuses on the icing and what is immediately under it while ignoring the bottom two layers. Yet these two layers are the ones that make the public and private sector possible and sustain it. (Cameron & Gibson-Graham, 2010; Frank et al., 2007)

Figure 1: Total productive system of an industrial society as a layer cake (Henderson, 2021)

Women still have a different position in the economy than men. They represent a smaller share of the paid labor force, have lower incomes, are in highly segmented employment groups and low-status industries, and take up a much larger share of unpaid economic activity (Donath, 2010). In Switzerland, for example, 9200 hours of unpaid work are performed per year. The paid work per year amounts to 7900 hours. Of this unpaid work 61% are performed by women and 39% by men (BFS, 2017). One of the consequences is that women have on average 37% less pension than men. Since occupational pensions are strongly linked to high earned income, structural inequalities from the labor market are directly transferred to retirement age. From a purely legal point of view, women and men might be equal – but not economically (Fluder & Kessler, 2017). And the main cause is, that the bearing and raising of children and the care of the aged and sick is still largely a woman’s responsibility (Donath, 2010).

From Either/Or to Both/And

Dualisms have strongly influenced the western conception of the order of the world. Mental shortcuts often harmlessly speed up our thinking, but they can also severely limit and bias our thinking. There is among others a deep cultural pattern of defining male as being opposed and superior to female and defining rationality as being opposed to and superior to nature, matter and emotion. Mainstream economics follow just such gender schematic pattern. In the layer cake, for example, icing and top layer are seen as masculinized, money-making and exploitative, while the bottom two layers are seen as feminized, governed by need and non-exploitative relationships. The model of the “economic man” is of an autonomous rational, self-interested actor, all interdependencies and emotions are excluded. Common habits of thinking tend to suggest that it is masculine and superior to see ourselves as beings who are above nature, and that good economics means distancing ourselves from each other and from ethical concerns.

Feminizing the economy has primarily involved adding a new layer to the market production and exchange – formally known as “the economy”. This would create a dualistic whole compromised of masculinized realm of paid work and feminized realm of unpaid, domestic, child-base, nurture-oriented, voluntary and community work. In these dualistic models, one side is privileged as source of emancipation while the other side is renounced. It adds to the picture of what contributes to the production of goods and services but does not necessarily help us think differently about economy. The added in sectors remain locked in a subordinate, devalued position vis-à-vis “the core economy”.

What we need is to dissolve the dichotomy, so that it is possible to see a greater diversity within layers of the economic cake and connections across what were previously thought of as separate and opposed layers. Instead of accepting the old either/or, we can get to a more nuanced and helpful both/and. Deconstructing the dualism itself, so that we see ourselves both co-members of an ecological community and yet different from other members of it. All humans are part of nature and constituted in our relationships, as well as able to think and act as human beings and individuals. We need a definition of economics that does not rely on either a masculine-biased definition based on markets and business firms, or masculine-biased definition based on rational choice theory, we need one that is based on provisioning. Economics should be about how societies organize themselves to provide for the survival and flourishing of life. (Cameron & Gibson-Graham, 2010; Nelson, 2009)

References

BFS. (2017). Satellitenkonto Haushaltsproduktion. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/arbeit-erwerb/erwerbstaetigkeit-arbeitszeit/vereinbarkeit-unbezahlte-arbeit/satellitenkonto-haushaltsproduktion.html

Cameron, J., & Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2010). Feminising the Economy: Metaphors, strategies, politics. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1080/0966369032000079569, 10(2), 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369032000079569

Donath, S. (2010). The Other Economy: A Suggestion for a Distinctively Feminist Economics. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1080/135457000337723, 6(1), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/135457000337723

Fluder, R., & Kessler, D. (2017). Warum Frauen weniger Rente erhalten als Männer. https://doi.org/10.24451/arbor.6879

Frank, A., Guha, S., & Yoneya, H. (2007). Total Productive System of an Industrial Society as a Layer Cake. http://avery.wellesley.edu/Economics/jmatthaei/transformationcentral/valuingthedevalued/valuedevaluedcake.html

Henderson, H. (2021). Valuing love economies. https://www.ethicalmarkets.com/valuing-love-economies-by-hazel-henderson/

Nelson, J. A. (2009). Between a rock and a soft place: Ecological and feminist economics in policy debates. Ecological Economics, 69(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOLECON.2009.08.021

Ringger, B. (2019). Die Globale Care-Gesellschaft.