Aline König

In the year 2050, about 10 billion people will live on Earth. By now many people suffer from hunger and in addition the global food system is a huge environmental burden which exceeds many planetary boundaries. So how is it possible to feed the population without further destroying the earth?

The Current World Food System

Today almost half of the global vegetated land is used by agriculture. Food production and associated land use changes are accountable for about a quarter of the annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In addition, this industry leads to nitrogen and phosphorus pollution, loss of biodiversity, and intensive water and soil use (Searchinger et al., 2014) which affects the stability of the earth system. Therefore, food production is the main cause of global environmental change. While agriculture has so far kept pace with population growth, more than 820 million people still do not have enough to eat or have a micronutrient deficiency. Simultaneously, some people eat too much food (Willett et al., 2019). When all those three forms occur together in a country, it is called a triple burden of malnutrition. This poses a major problem and challenge both for public health and development (Gómez et al., 2013). Various reports have concluded that a radical transformation of the global food system is needed to ensure healthy and sustainable diets for the population in 2050 and that this is inevitable to achieve the Paris Agreement as well as the SDG’s (The Eat-Lancet Commission, 2019). In this text, I briefly introduce two examples of such reports.

The Planetary Health Diet by the EAT-Lancet Commission

Figure 68.1 – Suggestion of how a plat of the “Planetary Health Diet” should look like (The Eat-Lancet Commission, 2019)

The EAT-Lancet Commission released a report on this topic in 2019. The Commission is made up of 37 scientists from around the world in the fields of food, health and planet. The Report focuses on the two main goals: “Healthy Diets” and “Sustainable Food Production”. For this purpose the authors elaborated a specific form of nutrition, the “Planetary Health Diet”. This diet is supposed to be optimal for human health as well as for the planet. It should mainly consist of plant-based foods and optionally be supplemented to a small extent with fish, meat or dairy products (Fig. 1). The “Planetary Health Diet” represents a rough guideline, which is open to local interpretation and adaptation to consider cultural and geographical aspects. Furthermore, a diet consisting mainly of plant-based food is unrealistic for countries struggling with malnutrition. Therefore, the amount of meat consumption is relevant in the context of the particular region or country. Besides the “Planetary Health Diet” the Commission has its focus on improved food production practices, and reduced food waste or loss. The report elaborated five strategies for a global food transformation. These include, for example, “seek international and national commitment to dietary change”, like the “Planetary Health Diet” or “sustainably intensify food production to increase high-quality output”. Another strategy bases on the protection of biodiversity and aims saving natural ecosystems and species-rich forests from the conversion into new agricultural land (Willett et al., 2019).

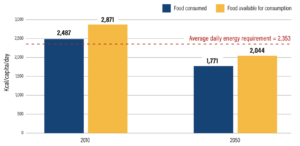

Figure 68.2 – Comparison of the food (in kcal) available in 2010 with the food necessary in 2050 (Searchinger et al., 2014)

In conclusion it is both possible and necessary to feed the 10 million people on this earth by 2050 in a sustainable way. However, data strongly indicates that this requires a fundamental change in the global food system and a close cooperation between the various parties, such as governments, businesses and consumers. The ideas that are outlined above are only small excerpts from two different reports and there are many other ideas and strategies. In the end there is no right or wrong and it is not essential which approach is chosen, but rather that a global decision is made as soon as possible and that it is implemented with concrete actions. This is the only way to ensure a diet that is healthy and sustainable for the population in 2050 and the only option to comply with the SDGs set by the UN as well as the Paris Agreement.

References

Gómez, M. I., Barrett, C. B., Raney, T., Pinstrup-Andersen, P., Meerman, J., Croppenstedt, A., Carisma, B., & Thompson, B. (2013). Post-green revolution food systems and the triple burden of malnutrition. Food Policy, 42, 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.06.009

Searchinger, T., Hanson, C., Ranganathan, J., Lipinski, B., Waite, R., Winterbottom, R., Dinshaw, A., Heimlich, R., Boval, M., Chemineau, P., Dumas, P., Guyomard, H., Kaushik, S., Makowski, D., Manceron, S., & Ben, T. (2014). Creating a sustainable food future. A menu of solutions to sustainably feed more than 9 billion people by 2050. World resources report 2013-14: interim findings. World Resources Institute, July, 558.

The Eat-Lancet Commission. (2019). Food Planet Health. The Lancet, 32.

Willett, W., Rockström, J., Loken, B., Springmann, M., Lang, T., Vermeulen, S., Garnett, T., Tilman, D., DeClerck, F., Wood, A., Jonell, M., Clark, M., Gordon, L. J., Fanzo, J., Hawkes, C., Zurayk, R., Rivera, J. A., De Vries, W., Majele Sibanda, L., … Murray, C. J. L. (2019). Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet, 393(10170), 447–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4