Maria Enarson

In uncertain times of soil degradation, climate change and a steadily growing population it is crucial to re-think our land usage in order to protect both people and planet. One way of bringing more stability into our agricultural systems are food forests: Let me walk you through this utterly interesting new – or old? – concept of farming.

What are Food Forests?

The name actually explains it quite precisely: Food Forests are forests, that produce food. So, they are a new form of agriculture, respectively a form of agroecology, that focuses on growing foods in a way that imitates a natural ecosystem. Their main characteristic is the concept of farming on multiple layers, in contrast to traditional farming that focuses on cultivating one type of crop on one layer.

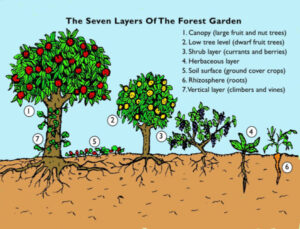

The seven common layers that are considered when a food forest is planned are illustrated below:

The seven layers of a Food Forest (Food and Trees for Africa: https://trees.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/7-seven-layers-food-forest-600×457.jpeg) Quality was reduced during upload.

The Canopy Layer consists trees of around nine meters in height. Usually, they produce fruit and nuts or are used for nitrogen-fixation purposes.

- The Low Tree Layer contains lower, usually fruit trees that reach about three to five meters in height.

- The Shrub Layer produces berries, fruits and nuts and is planted loosely around the smaller trees. Alternately, it can also contain medicinal and flowering shrubs.

- In the Herbaceous Layer, perennial herbs, like medicinal herbs or such used as bee-forage are planted.

- The Layer just above the soil surface is covered by low-growing crops and plants to protect the soil and prevent weeds form growing.

- The Rhizosphere Layer is also taken into consideration by planting foods that grow underneath the soil surface and therefore maximizes the use of the space.

- Last but not least, the Vertical Layer consists of plants that climb the trees, like vines, beans and suchlike.

There are many other possibilities though. For instance, it is also possible to add wetland or fungal layers, sometimes even livestock. (cf. de Groot & Veen, 2017)

The sunny and the shadowy Sides of Food Forests

So why should we think about Food Forests as a potential agriculture form of the future? They can generate a large output of very different types of food due to the production on many different layers.

They also contribute to the local biodiversity compared to our traditional monocultures. Not only directly, by simply having more types of food-producing plants in one area, but also indirectly through the creation of habitats for insects, as an example. (cf. de Groot & Veen, 2017)

Moreover, this form of farming directly addresses the urgent problem of soil degradation, which is a result of our current form of land usage. This semi-natural vegetation type that covers the soil all year round makes the soil less exposed to wind and water erosion, as well as it enables the natural soil functions to work the way they should: The mixture of different plants, some nitrogen-fixing, some with high nutrient requirements, some perennial and some annual, use and root the soil in very different ways and therefore ensure a its long-term quality as well as it prevents desertification.

Therefore, food forests can help us stabilize at least a small part of two things that the world is losing at a rapid pace: Biodiversity and fertile soil. The fact that trees fix some carbon dioxide is also a nice plus.

In addition to the environmental aspects, this type of land usage includes the local people, rather than keeping them away: Would you even think about taking a walk on your neighbouring farmer’s grain field? In food forests, recreation purposes such as walks and picnics are often even part of the concept. This is not only a luxury for the locals, but it can also help in raising awareness for an abundance of issues: The importance of healthy ecosystems that fulfill their multiple functions and scarcity of them is only one example. (cf. Urbane Waldgärten, n.d.)

However, the implementation of food forests also faces some challenges. The first of them comes at the beginning: As we all know, it takes quite some time for trees to grow tall. Consequently, it takes around five to ten years for a Food Forest to reach a productivity level that can be considered profitable.

Also, as one can imagine, the management, maintenance and harvest of Food Forests is more time-consuming and needs more manpower per surface unit than a traditional monoculture does: Machinery cannot really ease the maintenance and harvest, and in addition, the planning of them requires lots of knowledge.

And in the end, even though there are lots of crops and food-producing plants that can be cultivated in this concept, some of them just aren’t. Some staple foods such as grains are not suitable for this kind of agriculture, which is why food forests most likely won’t be the one and only type of agriculture in the future. If the aim was to produce foods in Food Forests, a change of our diet culture would be required to reduce the grain, meat and fish consumption. (cf. de Groot & Veen, 2017) If that is likely is debatable.

Nevertheless, we might want to consider this form of farming as an addition to other ones. The more variety there is, the better we can protect future soil fertility, which is key for any food production.

A new idea?

Even though the idea of Food Forests sounds very modern and innovative to our young, European ears, it has been used in many parts of the world for a very long time. Especially in areas where moisture is a limiting factor, rather than sunlight, agroforestry in the form of Food Forests has been a more attractive alternative to the monoculture that we are used to nowadays. In Central America, for instance, have used the benefits of forest structures on their farming plots: Coconut and papaya trees as a canopy layer, followed by citrus or banana, a shrub layer of coffee or cacao, tall and low annuals such as maize and finally a layer of squash or a similar plant to cover the soil surface. In this way, farmers were able to grow a large amount of foods on a rather small plot, by using many layers. Through the imitation of rainforest structure as well as its diversity, the stability of the ecosystem could be kept over a long time and erosion of these very fragile, tropical soils could be prevented. Similar types of agroforestry has been applied in Africa, in places like southern Nigeria, Zambia and in places in Asia, such as in the Philippines for a long time. (cf. Steppler & Nai, 1987)

Figure 64.2 – A Food Forest in a typical European agricultural area (EssWaldLand: https://esswaldland.ch/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/FoodForest-Ketelbroek.jpg)

We can see that in many tropical areas of the world, the concept of Food Forests is nothing new. But also in Europe, different forms of agroforestry has been used for centuries: Silvopastures, livestock farming in forests, to name one example. (cf. Smith, 2010) However, the idea of growing several layers that are all somehow edible is quite new in this part of the world. But it’s being tried! 222 Food Forests with an area of 501 hectares have been planted only in the Netherlands (Voedsel Uit Het Bos, n.d.). One example is an area of 30 hectares in Oosterwald, Almere, that was planted as part of a public nature area (de Groot & Veen, 2017). But also in Switzerland, there are several implementations as well as attempts to implement food forests as a part of our landscape. Project EssWaldLand is one of the groups that are active in Switzerland (Weiss et al., n.d.).

What can we expect?

Concluding, it might be unrealistic to implement Food Forests as the main source of agricultural goods in our part of the world. However they might form a reasonable alternative to mix in here and there, to get some variety into both our landscape and diet. And for some tropical parts of the world, where agroforestry once was widely rooted and could inhibit the loss of fertile soil, we can hope for its revival.

Bibligraphy

de Groot, E., & Veen, E. (2017). Food Forests: An upcoming phenomenon in the Netherlands. URBAN AGRICULTURE MAGAZINE, 33(Urban Agroecology), 34–36.

Smith, J. (2010). The History of Temperate Agroforestry.

Steppler, H. A., & Nai, P. K. R. (1987). Agroforestry – a decade of development.

Urbane Waldgärten. (n.d.). Retrieved May 17, 2022, from https://urbane-waldgaerten.de/

Voedsel uit het Bos. (n.d.). Retrieved May 17, 2022, from https://voedseluithetbos.nl/

Weiss, D., Landolt, M., & Lis, D. (n.d.). EssWaldLand. Retrieved May 17, 2022, from https://esswaldland.ch/