Gina Saccavino

New law regarding agriculture will enter into force by 2023. The recent decision from the Swiss federal council concerning the precise figures and regulations did not only lead to happy faces. Why not analyse this new law with the help of the SDGs by myself?

Historical background

The Swiss federal council’s decision on 13th April 2022 ruffled some feathers as the reaction of the Swiss Farmer’s Association showed (SBV, 2022). Farmers and agricultural organisations alike are outraged how strict the federal council has decided in the so-called parliamentarian initiative 19.475 or shortly paiv. This paiv was the outcome of the unofficial counter suggestion of the Swiss parliament to the two people’s agricultural initiatives in June 2021 (Agridea, 2022). The people’s agricultural initiatives claimed clean tap water and even a pesticide-free country but did not succeed. Now the “Absenkpfade” or flushing paths regarding nutrients and pesticides with additional regulations fostering biodiversity and soil health found their way into Swiss law. The federal council just publicly announced which precise reductions, measures and percentual rates must be met to fulfil the regulations to earn subventions.

As mentioned above, not everyone is happy with the recent decisions which would suggest digging deeper and analyse the decisions and their possible outcome by 2030. Why not taking the most interesting SDGs in this context as a measurement to properly do so?

Income and calories

The simulation of Agroscope (Mack & Möhring, 2021) predicts a change in overall farmer’s income in Switzerland by 2026 because of the paiv. They have analysed how overall farmer’s income would be impacted if the paiv was implemented. As a reference they simulated the overall farmer’s income impacted only by the agricultural politics from 2018 to 2021. In both scenarios the overall farmer’s income would rise, but in the paiv scenario the income would rise less than in the reference scenario (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Overall farmer’s net income with the reference and paiv scenario (Mack & Möhring, 2021)

The difference makes up about 2% over a period of four years. This is only a small difference but agricultural income is regarded rather low. This is shown by Jan et al. (2021) by taking comparison income (=Vergleichslohn in German) of agricultural employees from the family into account. They stated that these people only earn 85% (valley region), 64% (hilly region) and 56% (mountain region) in comparison to second or third sector employees. Of course, Swiss farmers are not regarded as poor and the paiv will not lead them into poverty but SDG 1, ending all forms of poverty, also consists of building economic resilience. This might be reduced a little bit by the paiv as the overall income may rise less compared to the reference scenario or said differently, the paiv does not contribute to SDG 1. In addition and with the same arguments as above the paiv does not contribute or even works mildly against SDG 8, promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all and SDG 10, reduce income inequality within and among countries.

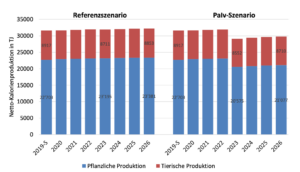

The paiv does increase ecological resilience by rewarding practices which restore soil. The paiv also financially supports the abandonment of pesticides and bans pesticides with high risk potential. (Agridea, 2022) These two measurements will decrease the net calorie production of plant-based produce and with that the overall produced net calories in Switzerland as seen in Figure 2 (Mack & Möhring, 2021). SDG 2, zero hunger, consists of increasing agricultural productivity. This leads to a rather mild or no contribution to SDG 2 because the agricultural output, here in calories, on the same amount of area will decrease.

Figure 2 Net calorie production with reference and paiv scenario (Mack & Möhring, 2021)

Pesticides and nutrient leak

One part of SDG 3, ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages, is reducing illness and deaths from hazardous chemicals. Mack & Möhring (2021) have shown that the financial support for abandoning pesticides will make it economically interesting for farmers. They therefore suggest that in the paiv scenario 45% of arable land will be used without pesticides which is 75% more than in the reference scenario. It was shown that the application of pesticides correlated with lung cancer (Alavanja et al., 2004). In Switzerland this risk is lower due to better education and protective equipment but if pesticides are handled and applied improperly, there are health risks associated (Zandonella et al., 2014). Because of this, the paiv contributes to SDG 3.

One part of the paiv prescribes that the sector may also contribute to the 20% reduction in nitrogen and phosphorus surpluses. In addition, manure should be promoted and thus reduce the use of synthetic fertilizers. To meet both goals, reduction in surpluses and promoting manure, the efficiency of manure should be increased because manure and the management of manure show high losses, especially of ammonia (LID.CH, 2015). Therefore, the paiv contribute to the achievement of SDG 12, ensure sustainable consumption and production pattern. The main goal of the paiv is to secure safe tap water in Switzerland by reducing nutrient and pesticide leak. To me, it is not clear how small or big the impact of nitrogen losses and the use of pesticides in Switzerland are on marine ecosystems such as seas and oceans. Other water ecosystems such as rivers and lakes are not mentioned in SDG 14 but the paiv will eventually improve the quality of these in Switzerland. Eventually, higher quality in rivers and lakes will lead to higher quality in seas and ocean. Therefore, the paiv mildly plays a role in achieving SDG 14, conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development. The risk reduction in pesticides and reduction in nutrient leak contribute to SDG 6, ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. More precisely to the targets of water quality improvement and protection of water-related ecosystems.

Biodiversity and climate change

The paiv supports practices that increase humus ratios in soils. This will bind carbon and thus contribute to climate mitigation. Additionally, it will improve the water-holding capacity of the soil and with this will lead to higher resilience. (Agridea, 2022) With this, the paiv helps achieving SDG 13, take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts by regulating emissions and promoting developments in renewable energy. The paiv demands 3,5% biodiversity area per agricultural crop land and reduces nutrient inputs in sensitive ecosystems. These ecosystems normally show low to very low nitrogen or overall nutrient levels and thus provide room for a lot of species. Moreover, grains sowed in a way that several rows are not sowed with grains but with flowers offer slippage for ground breeding birds and rabbits. Thus, natural habitats and biodiversity are fostered. These will lead to a contribution to SDG 15, protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss.

Fig 3, Outlook for Swiss agriculture, (Gina Saccavino, 2021)

Especially ecological aspects such as ecosystems, biodiversity, nutrient inputs and natural habitats are very well met. Economic elements, first and foremost the farmer’s income, are not met that well. In addition, the reduction of produced calories may interfere with the SDGs. Overall, I guess the paiv can be considered well done in the light of the SDGs. It remains to be seen how well Swiss agriculture will handle the new situation and whether a lower increase in farmer’s income and lower calorie production will be noticeable.

References

Agridea. (2022). Absenkpfad PSM und Nährstoffe Pa. Iv. 19.475. Retrieved from https://agripedia.ch/focus-ap-pa/de/startseite/absenkpfad-pflanzenschutz-und-naehrstoffe-pa-iv-19-475/absenkpfad-pflanzenschutzmittel-und-naehrstoffe/

Alavanja et al. (2004). Pesticides and lung cancer risk in the agricultural health study cohort. American Journal of Epidemiology, 160(9), 876–885.

Jan, P., Schmid, D., Dux, D., Renner, S., Schiltknecht, P., & Hoop, D. (2021). Die wirtschaftliche Entwicklung der schweizerischen Landwirtschaft 2020 (No. 409 / 2021). (rtsch). Retrieved from https://www.newsd.admin.ch/newsd/message/attachments/68446.pdf

LID.CH. (2015). Die wichtigsten Dünger. Retrieved from https://www.lid.ch/medien/dossier/detail/artikel/3-die-wichtigsten-duenger/

Mack, G., & Möhring, A. (2021). SWISSland-Modellierung zur PaIv 19.475: «Das Risiko beim Einsatz von Pestiziden reduzieren». Retrieved from https://link.ira.agroscope.ch/de-CH/publication/46245

SBV, 2022. (2022, April 13). Unbegreifliche Entscheide des Bundesrats. Retrieved from https://www.sbv-usp.ch/de/unbegreifliche-entscheide-des-bundesrats/

Zandonella et al. (2014). VOLKSWIRTSCHAFTLICHE KOSTEN DES PESTIZIDEINSATZES IN DER SCHWEIZ PILOTBERECHNUNG. Retrieved from https://umweltallianz.ch/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/vw_kosten_pestizideinsatz_schlussbericht_infras_de.pdf