Alejandro Valero

Recent events like the Russo-Ukrainian war, have shaken the strategies in the countries neighbouring Switzerland, which are starting to see nuclear power as a more attractive source in order to avoid resource dependence from Russia. That, together with the unexpected EU proposal to recognise both gas and nuclear energy as climate friendly at the end of 2021, sparked Switzerland to a position in which it could reconsider nuclear power as an energy source to become CO2 neutral and energy independent in the near future.

Figure 41.1 – Leibstadt NPP (source: The feasibility of phasing out nuclear power in Switzerland | EBP | Swiss)

Facing challenges such as limited supply of natural resources, increasing population, and the need for action on climate change policies, Switzerland needs a decided strategy to progress to the next step in energy production, with a clean climate-friendly system but also ensuring its independence from other countries resources.

But in Switzerland, as in many developed countries, nuclear power has always been a very controversial issue, even more since the Fukushima accident in 2011, which showed again the risks of nuclear power plants in case of catastrophe. Since then, the Federal Council of Switzerland decided to gradually move away from nuclear energy. The last Swiss nuclear power plant built was Leibstadt, which was first activated back in 1983. Since then, the nuclear power production infrastructure of the country hasn’t seen any important expansion (Romerio-Giudici, 2007).

What does nuclear power mean for Switzerland today?

As of today, nuclear energy is a third of the total Swiss electric power production (Swiss federal Office of Energy, 2020). It means the second largest source after hydropower, which constitutes a total of 58,1% between accumulation and run-of-river power stations. The substitution of such a large energy source raises some concerns. Which kind of sources will supply that needed energy? How many of them will be CO2 emitters?

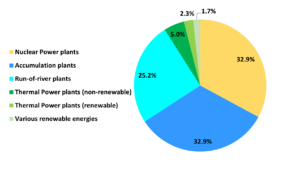

Figure 41.2 – Electricity production in 2020 by power plants categories (sources: Schweizerische Elektrizitätsstatistik 2020)

As of now, nuclear power plays an important role in Switzerland, but it is losing relevance with the time. Since 2018, nuclear energy has decreased from 36,1% to 32,9% by 2020 as seen in Figure 42.2. This decrease in recent years has been mainly affected by the shutdown of the Mühleberg nuclear power plant. Currently the nuclear energy production in the country comes from 5 reactors in 4 nuclear power plants: Breznau-1 and 2, Gösgen and Leibstadt (Kernenergie, 2022). The amount of these power plants won’t increase in the future, as part of the plans of the Energy Strategy 2050 (Swiss federal Office of Energy, 2021a).

The plan under the Energy Strategy 2050 is to maintain the operation of the still working nuclear power plants as long as their security is guaranteed, until they get to their end of life, like in the case of Mühleberg. At the same time, the Swiss government won’t give any more licences for new nuclear power plant constructions.

Thus, for now, the direction that Switzerland has taken is towards a withdrawal from nuclear energy, which has been the most common strategy for the rest of the countries in Europe, like Germany (World Nuclear Association, 2022a) or (in an even more decided way) Italy, which started the withdrawal back when the Chernobyl accident in 1983 happened and nowadays doesn’t count with any nuclear power plant (World Nuclear Association, 2021). On the other side, France is the greatest example of following the pro-nuclear power path, with currently 70% of its electricity production sources coming from nuclear power (World Nuclear Association, 2022b). France has shown that nuclear energy helps in the achievement of energy independence, and they are willing to continue that way, with the recent announcement of new reactor construction programs. Their vision is to achieve a future energy mix, composed of both nuclear and renewables (France 24, 2022).

Looking at Europe

Things quickly began to change in 2022. The EU’s unexpected proposal to recognise both gas and nuclear energy as climate friendly at the end of 2021 (DW News, 2022a), sparked discussion among the EU member states. Since then, the topic about a nuclear revival has been kept around.

Moreover, with the current crisis in Ukraine, many European countries are trying to reduce their natural gas imports from Russia (IEA, 2022). Some of them have seen that maintaining nuclear power can be a useful tool in this situation, which would mean stopping the nuclear phase-out in the short term, although it is still too soon to know if it could become a real change in the long term plans in European countries (Energy Monitor, 2022).

These changes are affecting the population, showing an increased support to keep nuclear power plants active (DW News, 2022b). Although this support is shown in response to the Ukrainian conflict, it could become in the future a preference against natural gas imports in general, which is often imported from non-democratic states. But there is another side effect from the Ukrainian conflict. Fears of a nuclear war are growing in Europe and potential damage to ukrainian power plants as in the case of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant (Brumfiel, 2022).

The high costs for building nuclear power plants are also strongly limiting the future of this source. This limitation has led to the research of new designs for smaller but cheaper nuclear power plants (Eath-Gates et al., 2020). The new technological advances could really help to improve the atractiveness of this industry for future investment.

As the environment around Switzerland is changing, it can influence the future public opinion on nuclear energy, which has been for now one of the main issues against the nuclear power industry together with the high economic costs.

Public acceptance

In order to consider the possibilities of reintroducing the construction of nuclear power plants, it is capital to analyse one of the main reasons that has made the government take action against it, which are, as introduced before, the public opinion on this energy source, and its acceptance to continue using it for a longer time.

The great shift in popular opinion about nuclear power was back in 2011, in the aftermath of the nuclear disaster at Fukushima. The event has led to a generalised negative perception towards nuclear power, which was the reason for the development of the Energy Strategy 2050, which has since the beginning enjoyed an important support. With 58.2% of votes in favour and 41.8% against in the May 21 of 2017 referendum, the Energy Act was passed (SWI, 2017). But the result wasn’t very unequivocal, as with less than a 10% difference, the opposition is important and it could mean that the support can change to a majority on the other side. And indicative of this is the nuclear initiative referendum held on the 27th of november 2016, just 6 months before the Energy Act, which proposed the imposition to shut down all nuclear power plants after no more than 45 years of operation. It would mean that the last nuclear power plant, Leibstadt, would close in 2029, finishing all nuclear energy production in Switzerland. The result this time was against the initiative, with a 54.2% of votes against and 45.8% in favour (SWI, 2016). These are quite close results and show the issue is far from reaching a consensus in the population. Thus, in the next referendums results could change and, with new proposals coming in the near future as the storage of high-level nuclear waste in Switzerland (Swiss federal Office of Energy, 2021b).

Conclusion

The door is still open for changes in the direction that Switzerland will follow. If the current situation is capable of pushing the public opinion back to a slightly positive position, Switzerland could end up heading to a nuclear renaissance, following the path of countries like France. The political environment around the nuclear issue is changing very fast, thus it makes it very difficult to foresee the outcome of it.

Sources

Brumfiel, Geoff. (2022). Video analysis reveals Russian attack on Ukrainian nuclear plant veered near disaster. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/03/11/1085427380/ukraine-nuclear-power-plant-zaporizhzhia?t=1653238953072

DW News. (2022a). EU proposes labeling gas and nuclear energy as climate friendly. https://www.dw.com/en/eu-proposes-labeling-gas-and-nuclear-energy-as-climate-friendly/a-60308833

DW News. (2022b). Ukraine war sparks major shift in Germany′s energy opinions. https://www.dw.com/en/ukraine-war-sparks-major-shift-in-germanys-energy-opinions/a-61401277

Eath-Gates, P, M. Klemun, M, Kavlak, G, McNerney, Buongiorno, J, E. Trancik, J. (2020). Sources of Cost Overrun in Nuclear Power Plant Construction Call for a New Approach to Engineering Design. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2020.10.001

Energy Monitor. (2022). Will the Ukraine War change Europe’s thinking on nuclear?. https://www.energymonitor.ai/sectors/power/will-the-ukraine-war-change-europes-thinking-on-nuclear

France 24. (2022). Macron to announce new French nuclear power ambitions. https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20220210-macron-to-announce-new-french-nuclear-power-ambitions

IEA, International Energy Agency (2022), A 10-Point Plan to Reduce the European Union’s Reliance on Russian Natural Gas. https://www.iea.org/reports/a-10-point-plan-to-reduce-the-european-unions-reliance-on-russian-natural-gas

Kernenergie. (2022). Die Schweizer Kernkraftwerke. https://www.kernenergie.ch/de/schweizer-kernkraftwerke-_content—1–1068.html

Romerio-Giudici, Franco. (2007). Nuclear Power – The Swiss Experience. Coordinating European Security of Supply Activities (CESSA) ; Judge Business School, University of Cambridge, UK 13-15 december 2007, p 1-9.

SWI. (2016). Vote results: Nuclear power initiative. https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/vote-results-november-27th-2016/42592236?utm_campaign=teaser-in-article&utm_source=swissinfoch&utm_content=o&utm_medium=display

SWI. (2017). Swiss give green light for renewables and nuclear phase out. https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/vote-opener/43190762

Swiss federal Office of Energy. (2020). Schweizerische Elektrizitätsstatistik 2020. https://www.bfe.admin.ch/bfe/en/home/supply/statistics-and-geodata/energy-statistics/electricity-statistics.html

Swiss federal Office of Energy. (2021b). Deep Geological Repositories Sectoral Plan. https://www.bfe.admin.ch/bfe/en/home/supply/nuclear-energy/radioactive-waste/deep-geological-repositories-sectoral-plan.html

Swiss federal Office of Energy. (2021a). Energy Strategy 2050 once the new energy act is in force. https://www.bfe.admin.ch/bfe/en/home/policy/energy-strategy-2050.html

World Nuclear Association. (2021). Nuclear Power in Italy. https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-g-n/italy.aspx#:~:text=Italy%20is%20the%20only%20G8,nuclear%20build%20 program%20was%20planned

World Nuclear Association. (2022a). Nuclear power in Germany. https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-g-n/germany.aspx

World Nuclear Association. (2022b). Nuclear Power in France. https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-a-f/france.aspx