Bianca Stocker

Dubai. A city of fast cars, indoor skiing, skyscrapers, an astonishing amount of air-conditioning, and … sustainability? When you think of Dubai, sustainability is usually not a word you associate it with. So it comes as a surprise that, in 2015, Dubai built their first net-zero energy city, the Sustainable City. How did this phenomenon emerge?

Dubai – Most Sustainable City by 2050

For centuries Dubai was a small, poor fishing village and trading port (Kunzig, 2017). But then the oil industry and an overnight real estate boom enabled Dubai to become the city it is today (Garfield, 2018). In 2006, The United Arab Emirates (UAE) was declared as the country with the largest ecological footprint per person by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF, 2006). Since then, the population of Dubai has even doubled, and so has the number of cars on its roads (Kunzig, 2017). In 2015, Dubai ranked first place for sustainability in the Gulf Cooperation Council region, worldwide it placed 33rd out of 50 of the world’s leading cities that were included in the sustainable cities index of ARCADIS (Batten, 2015). In 2017, the “Energy Strategy 2050” was launched by the UAE government, which aims to bring its clean energy up to 44% (United Arab Emirates, 2021). Two years before, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the Ruler of Dubai, launched the “Dubai Clean Energy Strategy”. The main goal was to cover 75% of Dubai’s energy requirement with clean energy by 2050, making it the city with the world’s smallest carbon footprint (United Arab Emirates, 2021). The percentage of clean energy is to be increased step by step. In 2020 the goal was to reach 7% and in 2023 25% (Nasir, 2021). As of the beginning of 2022, 11.38% of Dubai’s energy mix consists of clean energy (Gulf Business, 2022).

The Sustainable City

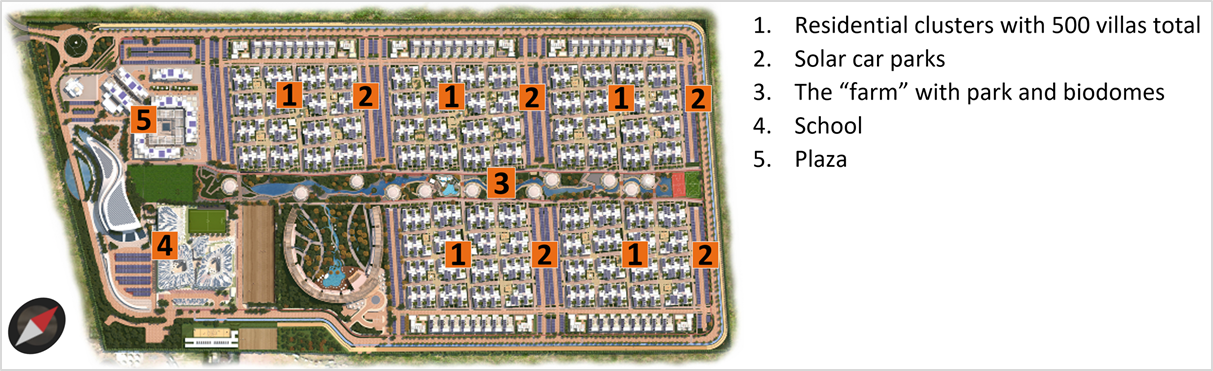

The 354M $ city, a designated area in Dubai, measures 0.46 km2 and consists of 500 villas with a total of 2700 residents (Mattei, 2019; Wikipedia, 2022). It offers a school, a plaza with cafes, restaurants and shops, carparks with solar panel roofs, a rehabilitation hospital, a sports complex, an outdoor pool and a beautiful park spanning the whole city. The area is surrounded by a wall consisting of 2500 trees, which purpose it is to purify the air and create a breeze (Fig. 39.1).

Figure 39.1 – The Sustainable City;

adapted from (The Sustainable City, 2019); source of compass: Google Maps

Since cars are heavily restricted inside the city, various sustainable transportation options, like public transport and communal electric buggies, have been implemented (The Sustainable City, 2019). For all the buildings and paths, a light shade of color was chosen to reflect the sunlight. The villas are oriented north to avoid direct sunlight and allowing them to receive a lot of shade (El-Jisr, Fully Charged Now, 2017). To support the local wildlife, lots of native trees were planted. There are 11 biodomes covering 3000 m2 spread throughout the park for urban farming (The Sustainable City, 2019). A simple system called “fan and pad” is used for cooling the biodomes, as portrayed in figure 39.2. Fans blow wind out of the biodome, creating a negative pressure inside. This then leads to air being sucked into the dome through the pads, which have been moisturized with water. The motors of the fans are powered using only solar energy (El-Jisr, Fully Charged Now, 2017).

Figure 39.2 – «Fans and Pads» cooling system (El-Jisr, Fully Charged Now, 2017)

Energy efficiency is a key aspect of the Sustainable City. The lighting is fully LED, which uses 10% of conventional lighting and is designed to decrease light pollution. All exterior lighting is powered by solar panels. The city uses energy efficient systems for heating, ventilation and air conditioning. Compared to conventional homes, the homes in this city require 50% less energy, 50% of which are provided by solar panels. All the rooftops and carparks are covered by the panels. The homes not only need less energy, but also the water consumption is reduced by 40% compared to conventional homes. The water gets recycled on-site and is reused for irrigation. Paper, plastic, glass, metal, cardboard, organic waste, anything that can be recycled will be recycled (The Sustainable City, 2019).

Critical view and conclusion

Since it was nearly impossible to find a critical view of the Sustainable City, I decided to write one paragraph, where I bring my view of the city, based on the research I did, in context with the SDG 11. One of its targets – 11.1 – is called “safe and affordable housing”. In Dubai, affordable housing remains an issue, even though there has been some residential development that focuses on the mid-market rent i.e., the low to middle income bracket. In 2017, for around 40% of households in Dubai the yearly income was approximately 100k $ (based on an 8.4k $/month salary over 12 months). This income category has been expanding in the last few years and is expected to continue doing so. For these 40% affordable rent is around 40.5k $ per year (Cooper, 2018). The rental costs in the Sustainable City vary between roughly 49k to 76k $ per year (MyBajut, n.d.). Regarding this, the villas in the sustainable city are unaffordable for the average Dubai household.

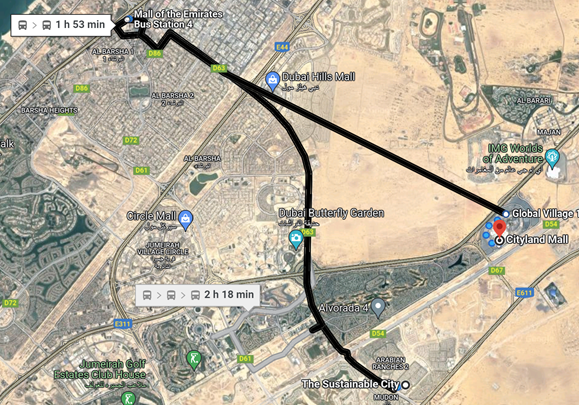

Figure 39.3 – Time to close-by mall by car (Google Maps, 2022)

Another SDG target is 11.2 – “affordable and sustainable transport systems”. Since the Sustainable City doesn’t offer many shops and opportunities for leisure activities and career options, people need to commute outside of the city. They do so by either taking their car or public transport. Dubai’s public transport network consists of two metro lines, a tram service and a bus network of over a hundred lines. There is a bus connecting the Sustainable city with other parts of Dubai (Roads & Transport Authority, 2022). But sometimes the public transport system fails. For instance, as figures 39.3 and 39.4 show, taking the car to the “Cityland Mall” takes about 12min whereas taking the bus takes almost 2h, which is roughly the same time it takes you to walk the 9.3km there (Google Maps, 2022). I was able to find a faster bus, but even then, it takes around 1.5h to get to the mall and the route is as inefficient as the one illustrated in figure 39.4 (Roads & Transport Authority RTA, 2022).

Figure 39.4 – Time to close-by mall by bus (Google Maps, 2022)

Overall, there are some very good sides to the Sustainable City, but in general, it appears to be a green bubble, shielding itself from the outside. Housing isn’t considered affordable, and although within the city there is no traffic, people still oftentimes use their car to reach certain infrastructure not available within the Sustainable City itself. When aiming to reach worldwide sustainability, this way of constructing cities is not the best way to achieve that goal. Instead of focusing on one neighbourhood and making it as perfect as possible, improving an already existing area could be better for the future of sustainable cities and communities.

References

Batten, J. J. (2015, February 1). ICMA. Retrieved from https://icma.org/documents/arcadis-sustainable-cities-index

Cooper, M. (2018). Deloitte. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/xe/Documents/About-Deloitte/mepovdocuments/mepov25/real-estate_mepov25.pdf

El-Jisr, K. (2017, March 18). Fully Charged Now. Retrieved from Youtube: https://youtu.be/WCKz8ykyI2E?t=705 (11:45 – 12:45)

El-Jisr, K. (2017, March 18). Fully Charged Now. Retrieved from Youtube: https://youtu.be/WCKz8ykyI2E?t=63 (1:07 – 1:33)

Garfield, L. (2018, January 29). Insider. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/dubai-sustainable-city-uae-2018-1?r=US&IR=T

Google Maps. (2022). Retrieved from https://www.google.ch/maps/dir/”/The+Sustainable+City+-+Dubai+-+Vereinigte+Arabische+Emirate/@25.0492134,55.274372,8895m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m14!4m13!1m5!1m1!1s0x3e5f6f91c1da7931:0x394244afc2fb1fb7!2m2!1d55.3032992!2d25.064275!1m5!1m1!1s0x3e5f702900225943:0x7

Gulf Business. (2022, January 17). Gulf Business. Retrieved from https://gulfbusiness.com/production-in-dubais-mohammed-bin-rashid-al-maktoum-solar-park-increases-to-330mw/#:~:text=Sheikh%20Mohammed%20bin%20Rashid%20Al,from%20renewable%20sources%20by%202050

Kunzig, R. (2017, April 4). National Geographic. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/dubai-ecological-footprint-sustainable-urban-city

Mattei, S. E.-D. (2019, March 28). Compass. Retrieved from https://wp.nyu.edu/compass/2019/03/28/shanti-escalante-dubai-sustainable-city/

MyBajut. (n.d.). Retrieved April 10, 2022, from https://www.bayut.com/mybayut/sustainable-city-dubai/

Nasir. (2021, February 15). logicladder. Retrieved from https://www.logicladder.com/2050-dubai-clean-energy-strategy/

Roads & Transport Authority. (2022). Retrieved from https://www.rta.ae/wps/portal/rta/ae/home

Roads & Transport Authority RTA. (2022, April 14). Retrieved from http://wojhati.rta.ae/dub/XSLT_TRIP_REQUEST2

The Sustainable City. (2019). Retrieved April 11, 2022, from https://www.thesustainablecity.ae/home/inside-the-city/

United Arab Emirates. (2021, April 20). The United Arab Emirates’ Government portal. Retrieved from https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/local-governments-strategies-and-plans/dubai-clean-energy-strategy#:~:text=In%20November%202015%2C%20Sheikh%20Mohammed,clean%20energy%20and%20green%20economy.

United Arab Emirates. (2021, October 12). The United Arab Emirates’ Government portal. Retrieved from https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/federal-governments-strategies-and-plans/uae-energy-strategy-2050#:~:text=The%20strategy%20aims%20to%20increase,AED%20700%20billion%20by%202050

Wikipedia. (2022, February 9). Retrieved April 13, 2022, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sustainable_City

WWF. (2006). Retrieved from https://wwf.panda.org/discover/knowledge_hub/all_publications/living_planet_report_timeline/lpr_2006/