Jan Keiser

It has been more than 25 years since Nelson Mandela became South Africa’s first black president. The end and the time after apartheid was heralded. But the problem of social inequality remains.

“It is not our diversity which divides us; it is not our ethnicity, or religion or culture that divides us. Since we have achieved our freedom, there can only be one division amongst us: between those who cherish democracy and those who do not.” (Mandela, 1999)

Picture 1: Nelson Mandela (Getty Images)

A view on the apartheid regime

Apartheid refers to race-based geography, known as spatial segregation, and politics. Nelson Mandela, a man whose quote we read above dedicated his life to the path of freedom and equality for South Africa’s oppressed black majority. For almost half a century, the brutal and discriminatory system of apartheid persisted in South Africa (Neumann-Bechstein, 2020). The country is known as the land of disparities. Just recently, there was a national éclat, as a school was dividing its students by their skin colour the first day of the semester (Schönherr, 2019). Not just in South Africa, but all over the planet, we are witnessing racial discrimination and the counter-movements, such as Black Lives Matter in the USA, are bringing the social explosive force back to the streets. More than 25 years after apartheid, it is time to take stock. Has the situation of black Africans really improved significantly since then?

Indicators of inequality

The level of inequality in South Africa is one of the highest in the world. It seems that poverty and inequality still have a racial undertone. There are two indicators of these circumstances:

The first indicator answers the question of whether the measures taken by the government are and have been able to reduce the level of inequality and poverty based on comparable household micro data. This is important to analyse the country’s transition to a post-apartheid society and to show the actual changes. Another important point is to quantify the legacy of the apartheid regime. (Leibbrandt, Woolard, Finn, & Argent, 2010)

The second indicator assesses whether the racial footprint in a modern post-apartheid South African socio-economy is fading (Leibbrandt et al., 2010).

Intra- vs. Between-race inequality

Socioeconomic realities still have their own dynamics of inequality. The current main problem is still that the social gap between whites and blacks is too wide. There are also large disparities within the different ethnic groups. Intra-African inequality and poverty trends are already prevalent. Strong inequality between races remains high and is decreasing only slowly. The intra-racial barrier prevents values from falling. Today, the greatest inequality exists within the African population and the least within the white population. This is not to say that the country’s racial footprint has disappeared; the racial component between blacks and whites remains remarkably high (Leibbrandt et al., 2010).

Historically, this was the result of direct racial privilege in state policies that determined where people could live and what education, health, and social services they were entitled to. Such spatial inequalities and inequalities in human capital leave a long-term legacy, and these processes are hard to reverse (Leibbrandt et al., 2010). There is something of a common agreement on the direction of inequality and poverty trends in the post-apartheid period, although precise quantification of poverty at different points in time is difficult (Leibbrandt et al., 2010).

The problem of the labour market

The signs of apartheid residues in the present are described by two key mechanisms. The unemployment and wage behaviour of the labour market is the first. Strong positive employment and real wage responses to economic growth are the main private sector poverty reduction mechanism. The second mechanism is the fiscal resources that growth provides to the state for active social policy and poverty reduction (Leibbrandt et al., 2010).

During an observation period between 1993 and 2008, there was hardly any significant decrease between the racial groups. The main problem seems to be that a large number of households do not have access to the labour market and therefore do not have sufficient income. In the initial phase after the end of the apartheid regime, there was even an increase in the unemployment rate. The poor did not benefit from the strong economic growth during this period. The lower the educational level and the number of employed persons of a household, the higher the poverty rate. Still, better-educated young people remain poor which suggests that the labour market has not been playing a successful role in alleviating poverty (Leibbrandt et al., 2010).

It was shown that social grants coming as financial support from the government have a positive effect on school attendance rates, health status and nutritional outcomes. The drawbacks are that those unemployed remain unemployed and are not covered by social grants. Expenditure on welfare and social assistance has increased substantially in the post-Apartheid period. Two-thirds of income of the bottom quantile now comes from social assistance, specifically child support grants (Leibbrandt et al., 2010).

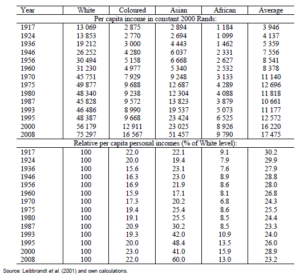

All in all, the labour market is at the centre of South African income inequality. The racial income inequality component remains remarkably high by international standards, and its decline has slowed since the 1990s. At any poverty line, Black Africans remain the poorest. The lowest deciles of the income distribution are dominated by Africans and are disproportionate to the population share (Leibbrandt et al., 2010).

picture 2: per capita income (Leibbrandt et al., 2010, p. 13)

In conclusion, it can be observed that overall inequality has remained obstinately high and may even have increased, due to racial inequality. More than 25 years of post-apartheid transition has not been enough time to work these factors out of South African society. It seems that South Africa needs to change its path, away from race-based redistribution to a more sustainable direction, in order to seriously address the growing inequality within the different ethical groups (Leibbrandt et al., 2010).

My impression is that the overall situation for the majority of black Africans in South Africa has improved only marginally. This is also reflected in last year’s unemployment rate; almost 40% of black Africans were unemployed, while the rate for the white population was almost five times smaller (Galal, 2022). It can be seen that the extremely complex processes and population structures of a country are difficult to change in a sustainable way because of large social differences. At least in the legal situation, Mandela’s vision was able to bring about a change in society, but the imminent improvement and release from the poverty line is likely to remain only a utopian idea for many in South Africa.

Sources

Galal, S. (2022). South Africa: unemployment rate by population group 2019-2021 | Statista. Abgerufen 31. März 2022, von Statista website: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1129481/unemployment-rate-by-population-group-in-south-africa/

Leibbrandt, M., Woolard, I., Finn, A., & Argent, J. (2010). Trends in South African Income Distribution and Poverty since the Fall of Apartheid. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, (101), 1–91. https://doi.org/10.1787/5kmms0t7p1ms-en

Mandela, N. (1999). Nelson Mandela’s Life & His Statements Speaking Out For Justice. Abgerufen 31. März 2022, von United Nations – Nelson Mandela International Day 18 July website: https://www.un.org/en/events/mandeladay/legacy.shtml#KeyStatements

Neumann-Bechstein, W. (2020). Geschichte Südafrikas: Apartheid – Afrika – Kultur – Planet Wissen. Abgerufen 31. März 2022, von planet-wissen.de website: https://www.planet-wissen.de/kultur/afrika/geschichte_suedafrikas/pwieapartheid100.html

Schönherr, M. (2019). Rassismus – 25 Jahre nach Apartheid: Warum Nelson Mandelas Erbe in Gefahr ist. Luzerner Zeitung. Abgerufen von https://www.luzernerzeitung.ch/international/25-jahre-nach-apartheid-warum-nelson-mandelas-erbe-in-gefahr-ist-ld.1359893