Raya Heusser

Even in a perceived as modern society as Switzerland, we are still far from true gender equality and there is still significant room for improvement. 31% of Swiss companies still do not have a woman in the top management and women in management positions still make some 20% less money than men (BFS, 2018).

Picture 1: «More time, more salary, more resepect». Demands of the labor union of the personnel of public transportation at the equal’s right demonstration in Bern, June 14, 2021

Historical game-changers

Switzerland has come a long way: It was only 51 years ago that Switzerland finally introduced the women’s right to vote, followed by the establishment of the principle for equal rights for men and women in the Swiss constitution in 1981. Subsequently several transitions followed, such as the first women in the Swiss politics or the introduction of the statutory paid maternity leave, that shaped our society in a way to promote gender equality and women’s equal societal rights. The inequality declined substantially over those last 51 years (Dufrense, 2021).

Switzerland now ranks above average globally. The question remains if being better than average is good enough. Even in a perceived modern society such as Switzerland, we are still far from true gender equality and there is still significant room for improvement. A main reason is our traditional social structure with unequal share of daily jobs like domestic work, unpaid care, and parental responsibilities. Another factor is our traditional, hierarchical company structure which prevents the combination of part-time jobs and career (Focus 2030, 2020).

In the following paragraphs, I will outline the inequalities in the Swiss society and share some thoughts on a possible way forward.

Women, still at a disadvantage

Swiss society still suffers from the incompatibilities of family and career. Women in the age bracket of 20-35 years are clearly disadvantaged, because when they got a baby it is very possible that they get fired, as the employer sees it as a risk that they could have a second child and, after giving birth, be absent for a long time (Gnehm, 2019). This discriminates women considerably, as a person’s family situation does not influence their working conditions but still prevents women to enter the career path. Naming one’s family status or family plans on their CV or asking about it in a job interview is like an unwritten rule in Switzerland. In other countries, such as in the USA, age or family intentions are never written in a CV or asked for in a job interview. Comparably, women with no family plans can also use this unwritten rule as an advantage compared to other women, writing on their CV that they have no such plans. In their situation, this might be seen as a rational decision, long-term and for the society it discriminates women in general (Dufrense, 2021).

Making the decision about who to employ dependent on the gender and one’s family situation is not only discriminative, but also irrational from a companies’ perspective as companies are excluding a significant part of the potential talent pool.

Work family balance in Switzerland could be improved with more part-time career opportunities. For many positions one can only get hired as a full-time job, while for a good life-family balance it might be necessary for both parents to only work 50-70%. Still, in high-level positions part-time work is hardly ever an option (Focus 2030, 2020). Swiss companies still have a very strong culture which says that “the boss” needs to be an individual person , being available 7/24/365. This preference excludes people who aim to balance family and work but still want to make a career.

Our traditional hierarchical organizational structure is outdated. Modern and successful companies are much less hierarchical and hence also open for more flexible employment schemes, such as part time working or shared jobs. An ideal company structure would be a team, where a lot of people work together, and more than one person can fill a specific position. A paradigm shift would both be beneficial for the companies and for women as it would allow companies to address the full talent pool and would allow a proper work-family balance.

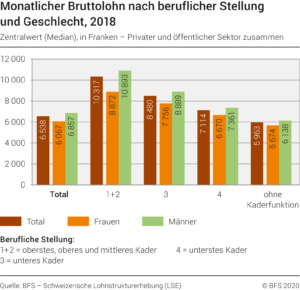

A significant salary difference remains between men and women in Switzerland. According to the BFS (Swiss federal institute of statistics) in 2018 there was an average gross salary difference of 20 + – 1%, which is an enormous number. As you can see in picture 2, the largest difference is observed in the upper and middle management. (BFS, 2018).

Picture 2: Gross salary difference between men and women in Switzerland. Orange = women, green = men, 1 + 2 = upper and middle management, 3 = lower management, 4 = lowest management.

There are also buckets of disadvantages for men

When talking about equality, people focus on the inequality for women, as this is the most burning issue. But we also must keep in mind that men also face inequalities in the Swiss society.

Men have to go to the army for at least 18 weeks, or if they refuse, they have to do equivalent work 1.5 times as long as the military service would last to compensate the army service. Women are not required to serve military duty, nor do they have to compensate for not doing so. Some might argue that this is historically “given”, but if we want to support equality either the mandatory army service for men should be abolished or women should have to conduct an equivalent social work. (Eidgenossenschaft, 1995)

Some companies introduced quotas requiring that some percentage, for example 30% of the overall employees or the top management, should be women. As nowadays those positions are mostly covered by men, this means that to improve those quotas, companies must hire primarily women.

Diving into the specific situation of top management functions an additional issue arises. According to BFS, in the year 1990 the female quote at Swiss universities was about 38.8% whereas the female percentage at a business university like HSG was around 25% (BFS, 2020). Assuming that a typical top management candidate is in the age bracket of 40-55 years, this means, that the available talent pool consists of 70% men and 30% women. As a consequence, an unemployed man of this age faces difficulties to get to those positions.

So, is it fair that we discriminate men on the short-term with the long-term goal of increasing equality?

Another inequality in the Swiss society is the maternity versus the paternity leave. Women get a leave of 18 weeks; men only get 2 weeks. For medical reasons it is obviously necessary that women get more time off than men because they need to recover from the pregnancy, from giving birth and to prevent from getting postpartum depression (Services, 2019). The evident inequality regarding this issue is that the paternity leave for men, compared to other countries, is extremely short and it is discriminating that men can’t spend a lot of time with their newborn child. This is based on and reinforces the mindset, that women are more responsible for family and taking care of the baby and men are more responsible for working and bringing the money home. The not so evident inequality is that the only 2 weeks paternity leave for men also puts the women at a disadvantage, because they have to look after the new-born alone, whereas they could also do this together or share the work.

Solutions

We need a paradigm shift and need to see gender equality as an asset rather than a liability. Obviously, quotas, awareness-building and laws help in achieving gender equality. Still, another element we should address is old patterns that are still maintained nowadays.

The current (Swiss) paradigm is still that large companies need to be built hierarchically and that there needs to be one boss who is available 7/24/365. As shown, this prevents part-time workers from making careers. However, it also hinders companies themselves from being successful as it prevents them from addressing the full talent pool.

To address the current challenges, we need non-hierarchical and agile company structures which allow more flexibility, part-time working, and group work. It would also allow companies to tap into the full talent pool and no longer limit them by only hiring “100% employees”.

Such a paradigm shift would then significantly influence our social structure, as it would allow more part-time working. This replaces old mindsets, where traditionally the man works full time and earns the money, while the woman takes care of the household and takes on a career limited part time job. In the future, both parents can combine family and career by working 50-80% each. If we want to become equal, we need to change that mindset and need to promote part time jobs more and also announce more part time job offers. Nowadays most of the job tendences are for full time jobs and people who would prefer to work part time do not even apply for it.

A solution for the maternity and paternity leave would be to give one leave for both parents. With this, they could share a certain amount of weeks between them the way they want to. This big change would then automatically lead to other changes such as that one no longer would have to ask about one’s family plans, because if both work part time at the end it would not matter if you employed men or women. Also, the company would not necessarily ask about the family status.

The conclusion of this big issue is that we still have potential for improvement and that the Swiss society needs to change its mindset in order to accept more modern structures. If this happens, it will then automatically lead to more equality.

Sources

BFS. (2018). bfs.admin. Von Lohnunterschied: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/arbeit-erwerb/loehne-erwerbseinkommen-arbeitskosten/lohnniveau-schweiz/lohnunterschied.html abgerufen

BFS. (2020). bfs. admin. Von Tertiärstufe – Hochschulen: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/bildung-wissenschaft/personen-ausbildung/tertiaerstufe-hochschulen.html abgerufen

Dufrense, A. (2021). swissinfo. Von https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/to-advance-gender-equality-in-switzerland–remove-family-status-from-cvs/46348678 abgerufen

Eidgenossenschaft, S. (1995). Admin. Von ZDG: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1996/1445_1445_1445/de abgerufen

Focus 2030. (2020). Switzerland. Von Women Deliver: https://focus2030.org/IMG/pdf/global_survey_gender_equality_switzerland_deepdive.pdf abgerufen

Gianella, K. (2022). Erfolgsfaktor Gender Diversity: Massnahmen und Hemmfaktoren.

Gnehm, C. (2019). Handelszeitung. Von Schweizer Firmen entlassen junge Mütter: https://www.handelszeitung.ch/beruf/schweizer-firmen-entlassen-junge-mutter abgerufen

Services, U. D. (2019). office on women’s health, postpartum depression. Von https://www.womenshealth.gov/mental-health/mental-health-conditions/postpartum-depression abgerufen