Shun Hei Lee

When we talk about sustainable food, the most common keywords include organic, local, plant-based, and fertilizer. What else is there? Equality seems to be the key principle that guides food systems to a sustainable future when considering farmers in the world, scientific domains and development finance.

When the term “sustainable food systems” is mentioned, what comes to your mind? People might say local production, some would mention “organic food”, and others might mention fair trade. Although these concepts are sometimes championed as great solutions to our global sustainability challenges, their actual implementation is not without limitations and controversies. Instead of proposing a one-fit-for-all solution or production method, we can think about ways to put equality as the focus of creating sustainable food systems.

Re-localization in a globalized world

People have been perceiving local production as a good approach to agriculture for quite some time. In recent years, people start to advocate for the re-localization of food production as an alternative to the globalized agricultural commodity trade, which indeed lacked transparency and traceability (Gardner et al., 2019; Zwart & Wertheim-Heck, 2021).

Ideally, re-localization can reduce consuming globally trade agricultural products and enable citizens to better understand the origins of the food they consume. Localized food systems have short supply chains and thus require less transport. Moreover, people can confirm that the local production does not cause significant environmental damage to the community. It can build confidence for people to purchase food sustainably, especially if a local farm is open for visitors. In terms of economics, localized food systems can even mitigate global food price and supply shocks and contribute to local and regional economies (El Bilali et al., 2021). Community-supported agriculture is a good example in which re-localization brings back social connection and create mutually beneficial relationships.

However, decoupling from our interconnected global trade is not as simple as disconnecting our laptops from the internet. The ripple effect of deglobalization/re-localization might cause a new wave of man-made disasters. Deforestation in the Amazon rainforest is an example of commodity-driven deforestation caused by agriculture. Here, the actual impacts happened at the beginning of the supply chain. Deforestation causes the loss of an essential terrestrial carbon sink and natural habitats (Tagesson et al., 2020). Farmers cleared out forests for soy farming, which was subsequently reduced after the implementation of the Amazon Soy Moratorium (ASM) (Kastens et al., 2017). The ASM involved the Brazilian Association of Vegetable Oil Industries, which represented soya traders and pledged not to buy soy that causes deforestation. The consumption of deforestation-linked soy was driven by European farmers using soy as fodder for animal production, such as chicken in the United Kingdom (The guardian, 2022). They would purchase soy from suppliers who comply with the ASM because retailers would require them to fulfill this standard. In theory, the ASM could reduce deforestation by selecting zero-deforestation soy suppliers. However, farmers discovered the legal loopholes and continued to clear out forests for growing other crops and agricultural commodities (Valdiones et al., 2022). It can be argued that the ASM unexpectedly generated social inequality, thereby weakening the social sustainability of the supply chain (Weinhold et al., 2013). Some farmers who did not have to deforest land for farming might already have very productive land and high-quality agricultural inputs, whereas other farmers with low occupational mobility could not survive their livelihoods other than farming unproductively in deforested lands as ASM did not provide them an alternative with adequate income nor knowledge capacity (Cabezas et al., 2019).

In the context of soy production in the Brazilian Amazon, we could see that transitioning to a sustainable food system requires more than re-localization. Investments in local infrastructure for storage, marketing, and processing is key for farmers to shift away from land degrading agricultural practices (Garrett et al., 2017). As 65% of poor adults in the world rely on agriculture, the debate on whether we should cut these farmers off from food production rather than facilitate their development deserves our attention (Castaneda et al., 2016).

Figure 1. Dutch market stands selling local food. “Streek” is the Dutch word for “region”. A product is “local” when it is produced within a certain distance, ranging from 15 to 100 kilometers. The definition of local products is not universal. The photo belongs to the author.

Embrace new perspectives

Research on sustainable food systems has been contesting our meat-based diets, which are ingrained in our modern consumption culture (Sabate & Soret, 2014). While people are transitioning to plant-based diets, we must ask the question: whose knowledge are we relying on? It is important for science communication to move away from the current simplistic interpretation of scientific outcomes about food sustainability. For example, the environmental impacts of food products were commonly measured based on the weight of each product. However, some articles adopted other approaches: measuring the environmental impacts based on the protein content or even essential amino acid content of the product (Poore & Nemecek, 2018; Smith et al., 2021). Incorporating nutrition science and other scientific domains into envisioning sustainable food systems can generate new insights and discourses, leading to different ways of thinking but not merely a dichotomy of plant-based and animal-based diets. A more equal representation of disciplines requires experts’ willingness to synthesize knowledge and acknowledge the limitations of their discipline, especially when using their expertise for policymaking (Nowotny, 2003).

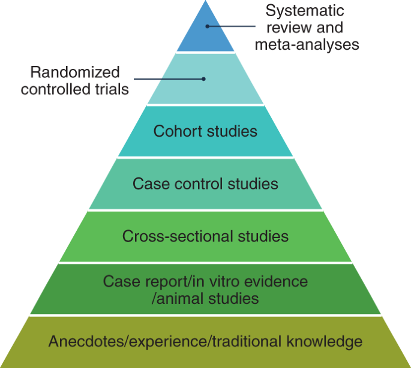

Apart from that, we need to ensure the representation of knowledge from different domains and knowledge production methods. Traditional knowledge, including the knowledge from indigenous people, is often overlooked and dismissed as non-scientific or of low quality (see Figure 2) (Milbank et al., 2021). Based on dominant research paradigms, people apply scientific-based policy solutions without considering the context and the limitations of their approaches. Although these knowledge productions might not involve the latest technologies, they can document the existing good practices. For example, it was discovered that indigenous people influence at least 28% of land and its biodiversity in the world (Garnett et al., 2018). If scientists are reflexive, new perspectives of science will enable us to develop more comprehensive solutions to sustainable food and land use.

Figure 2. The current hierarchy of knowledge production in food sustainability research. Reproduced from Milbank et al. (2021).

Explore synergies with development finance

Many food products now receive certifications to prove that their products meet certain principles, such as guaranteeing farmers’ livelihoods or using organic agricultural inputs. Sometimes it complicates people’s purchasing decisions. Do we need to make a choice between tackling income inequality and climate change? Not really. There are many synergetic solutions in which environmentally-friendly food production can lift people out of poverty. Development finance has become more integrated with climate change nowadays. For example, the World Bank, an international development organization that aims to reduce poverty with fiscal measures, pledged to have 35% of its finance related to climate change (World Bank, 2020). Research has also shown that “poverty and climate change be addressed simultaneously” through agroforestry and other agricultural practices (Jameel et al., 2022). Reducing inequality by financing agricultural SMEs in developing countries can alleviate unemployment and women’s lack of access to land and production inputs like irrigation (Agarwal, 2018; Palmer, 2016). These are also the conditions or, at least, important factors to environmentally-friendly food systems.

The implications of equality

Putting equality at the heart of sustainable food systems has huge implications. Policymakers need to understand the distribution of global impacts of sourcing food from different origins. The representation of scientific disciplines should be inclusive enough to challenge current discourses originating from previous research. Equality will also ensure that development finance will be spent in more sustainable ways and tackle several problems simultaneously.

References

Agarwal, B. (2018). Gender equality, food security and the sustainable development goals. Current opinion in environmental sustainability, 34, 26-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.07.002

Cabezas, S. C., Bellfield, H., Lafortune, G., Streck, C., & Hermann, B. (2019). Towards more sustainability in the soy supply chain: How can EU actors support zero-deforestation and SDG efforts. https://irp-cdn.multiscreensite.com/be6d1d56/files/uploaded/Sustainability%20in%20Soy%20supply%20chain_consolidated%20study%20%282%29_final.pdf

Castaneda, R., Doan, D., Newhouse, D. L., Nguyen, M., Uematsu, H., & Azevedo, J. P. (2016). Who are the poor in the developing world?. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (7844). https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-7844

El Bilali, H., Strassner, C., & Ben Hassen, T. (2021). Sustainable agri-food systems: environment, economy, society, and policy. Sustainability, 13(11), 6260. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116260

Gardner, T. A., Benzie, M., Börner, J., Dawkins, E., Fick, S., Garrett, R., … & Wolvekamp, P. (2019). Transparency and sustainability in global commodity supply chains. World Development, 121, 163-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.025

Garnett, S. T., Burgess, N. D., Fa, J. E., Fernández-Llamazares, Á., Molnár, Z., Robinson, C. J., … & Leiper, I. (2018). A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nature Sustainability, 1(7), 369-374. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0100-6

Garrett, R. D., Gardner, T. A., Morello, T. F., Marchand, S., Barlow, J., de Blas, D. E., … & Parry, L. (2017). Explaining the persistence of low income and environmentally degrading land uses in the Brazilian Amazon. Ecology and Society, 22(3). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09364-220327

Jameel, Y., Patrone, C. M., Patterson, K. P., & West, P. C. (2022). Climate–poverty connections: Opportunities for synergistic solutions at the intersection of planetary and human well-being. Project Drawdown. https://doi.org/10.55789/y2c0k2p2

Kastens, J. H., Brown, J. C., Coutinho, A. C., Bishop, C. R., & Esquerdo, J. C. D. (2017). Soy moratorium impacts on soybean and deforestation dynamics in Mato Grosso, Brazil. PloS one, 12(4), e0176168. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176168

Milbank, C., Burlingame, B., Hunter, D., Brunel, A., de Larrinoa, Y. F., Eulalia Martinez-Cruz, T., … & Dounias, E. (2021). Rethinking hierarchies of evidence for sustainable food systems. Nature Food, 2(11), 843-845. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00388-5

Nowotny, H. (2003). Democratising expertise and socially robust knowledge. Science and public policy, 30(3), 151-156. https://doi.org/10.3152/147154303781780461

Palmer, N. (2016). Making climate finance work in agriculture. World Bank Discussion Paper. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/986961467721999165/Making-climate-finance-work-in-agriculture

Poore, J., & Nemecek, T. (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360(6392), 987-992. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq0216

Sabate, J., & Soret, S. (2014). Sustainability of plant-based diets: back to the future. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 100(suppl_1), 476S-482S. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.071522

Smith, N. W., Fletcher, A. J., Hill, J. P., McNabb, W. C., & Pembleton, K. (2021). Animal and plant-sourced nutrition: complementary not competitive. Animal Production Science. https://doi.org/10.1071/AN21235

Tagesson, T., Schurgers, G., Horion, S., Ciais, P., Tian, F., Brandt, M., … & Fensholt, R. (2020). Recent divergence in the contributions of tropical and boreal forests to the terrestrial carbon sink. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4(2), 202-209. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-1090-0

The Guardian. (2022). ‘Loophole’ allowing for deforestation on soya farms in Brazil’s Amazon. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/feb/10/loophole-allowing-for-deforestation-on-soya-farms-in-brazils-amazon

Valdiones, A.P., Silgueiro, V., Carvalho, R., Bernasconi, P., Vasconcelos, A. (2022). Soy and illegal deforestation: the state of the art and guidelines for an expanded monitoring protocol in Mato Grosso. https://www.icv.org.br/website/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/relatorio-soja-desmat-ing.pdf

Weinhold, D., Killick, E., & Reis, E. J. (2013). Soybeans, poverty and inequality in the Brazilian Amazon. World Development, 52, 132-143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.11.016

World Bank. (2020). World Bank Group Announces Ambitious 35% Finance Target to Support Countries’ Climate Action. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/12/09/world-bank-group-announces-ambitious-35-finance-target-to-support-countries-climate-action

Zwart, T. A., & Wertheim-Heck, S. C. (2021). Retailing local food through supermarkets: Cases from Belgium and the Netherlands. Journal of Cleaner Production, 300, 126948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126948