In the classroom, peer assessment is a didactic method in which instructors design a structured feedback loop between learners to improve a learner’s submitted assignment. Reinholz writes, “peer assessment is defined as a set of activities through which individuals make judgements about the work of others” (2016: 301). It is important that in double-blind reviews, learners are ignorant of the status and reputation of their reviewers. In a class-setting, they usually are of equal status.

Some scholars differentiate between peer feedback as a “communication process through which learners enter into dialogues related to performance and standards” and relates to “rich detailed comments but without formal grades”, whereas peer assessment pertains to “students grading the work or performance of their peers using relevant criteria (Falchikov 2001)” and specifically “denotes grading (irrespective of whether comments are also included)” (Liu and Carless 2006: 280).

The term peer assessment is here used synonymous with peer review and peer grading. Peer review is a didactic method that supports socio-constructivist and connectivist learning processes, online or face-to-face, at all educational levels, in both formal and informal contexts. The idea behind the method is that sharing views and opinions with others by discussing with peers and receiving and providing formative feedback enriches the quality of learning (Pozzi et al 2016).

The general assumption is that peer assessment can sustain active and collaborative learning. It can, at the same time, combine “summative assessment (i.e. peers evaluate an individual’s work in order to assign a grade) and formative assessment (i.e. peers provide constructive feedback that could help an individual improve his or her work)” (Patchan et al 2017: 1). One of the big promises of peer assessment, that many authors point out, is that “multi-peer assessment can provide more total feedback than a single over-taxed instructor (Cho, Schunn, and Charney 2006; Patchan, Charney, and Schunn 2009; Patchan, Schunn, and Clark 2011).” (Patchan et al 2017: 1-2).

After several decades of (somewhat unsystematic) research on the topic, several studies have found that “students can provide feedback that is just as helpful as an instructor’s feedback in helping their peers improve their drafts (Topping 2005), and sometimes they can provide feedback that is more helpful (Cho and MacArthur 2011; Cho and Schunn 2007; Hartberg et al. 2008).”

Diana Laurillard (2012: 190) summarises peer assessment and peer feedback as an aspect of learning through collaboration. To better understand her approach to the didactic design and its effects on teaching and learning, it is helpful to let her summarize the aim of her Conversational Framework:

“The aim of the Conversational Framework is to represent, as simply as possible, the different kinds of roles played by teachers and learners in terms of the requirements derived from conceptual learning, experiential learning, social constructivism, constructionism, and collaborative learning, and the corresponding principles for designing teaching and learning activities in the instructional design literature. This is the simplest possible static visual representation that can capture the complexity of the collective ideas in the literature on what it takes to learn, and therefore what it takes to teach.” (Laurillard 2012: 93).

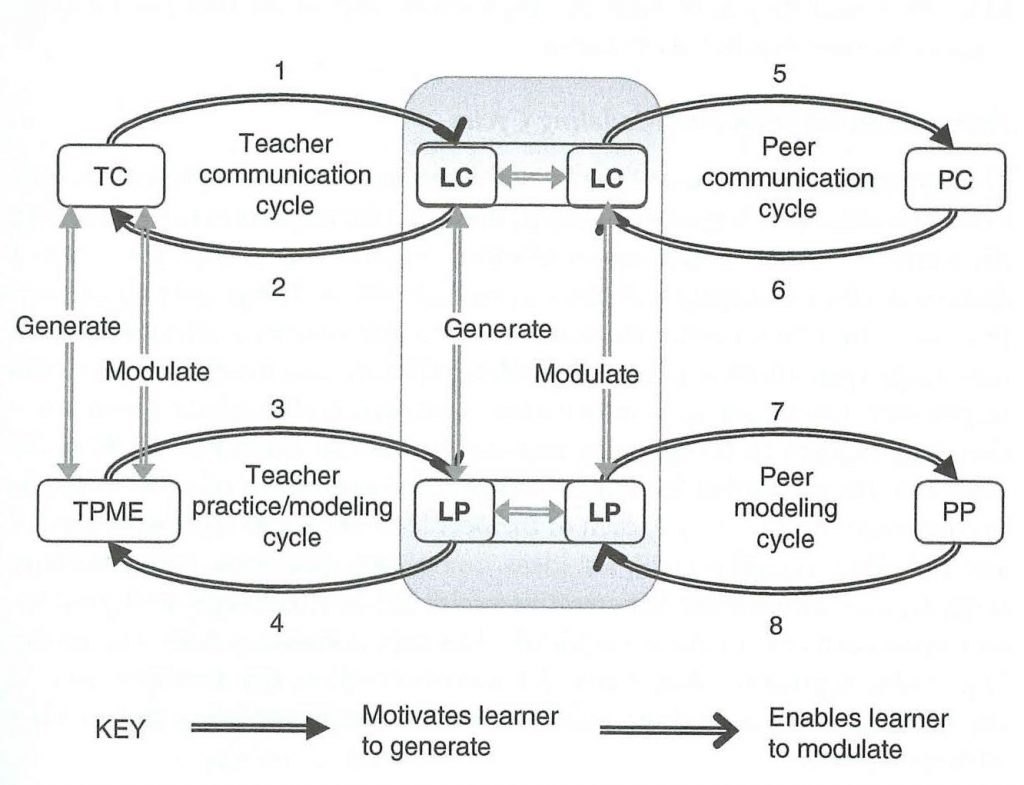

In the Conversational Framework that establishes the triadic figuration of teacher-learner-peers, she combines the peer communication and modeling cycles as follows:

“The importance of peer feedback also emerges in a more recent study that shows very clearly how the use of peer review can act as a valuable form of collaboration. Each student has to produce an output (in this case draft pages of an assignment), which is shared with two others for them to comment. The act of creating an output in order to share it plays a role in motivating the student’s practice, but being encouraged to engage in peer review of each other’s work establishes an iterative cycle of:

- seeing an alternative solution in the output of a peer;

- generating feedback for their peer;

- using the feedback from others to modulate their concept; and

- generating a new output as a result, which enables modulation of their practice.”

It connects teacher (left), learner (middle) and peers (right).

Figure 2.1 – The learner learning through interaction with peers’ concepts and practice (PC, PP), exchanging concepts and the out-puts of their practice (numbered components are defined later in the text). (Laurillard 2012: 90).

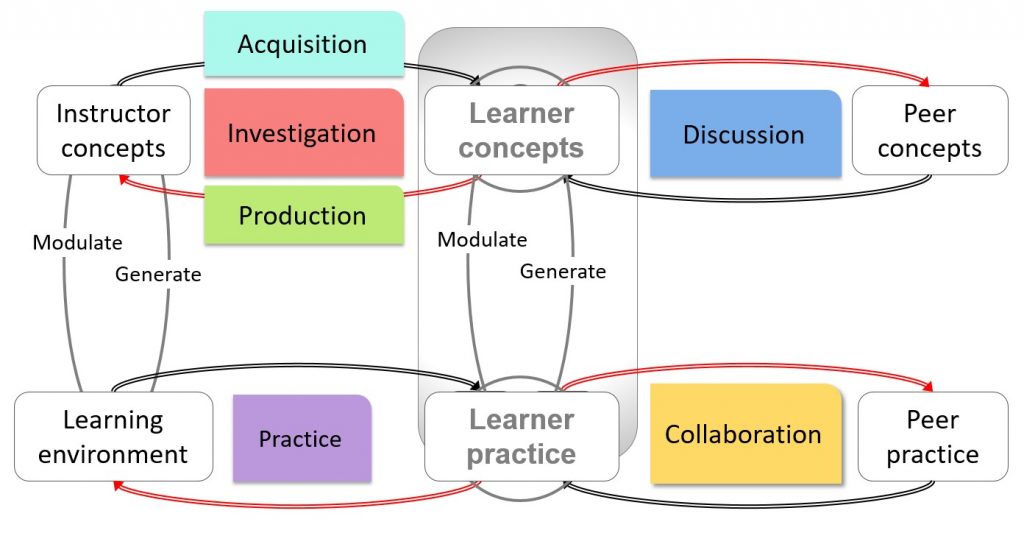

Peer assessment is a complex form of learning and usually touches upon multiple ways of learning within the conversational framework. The conversational framework is both a learning theory and a practical framework for designing educational environments. It outlines 6 different types of learning:

- ‘learning through acquisition’, where the teacher is communicating concepts and ideas;

- ‘learning through inquiry (investigation)’, where the learner explores or interrogates the teachers’ concepts;

- ‘learning through practice’, where the learner puts their concepts into practice to achieve a task goal, and then responds to feedback;

- ‘learning through discussion’, where the social construction of ideas helps them develop their concepts;

- ‘learning through collaboration’, where discussing and sharing practice helps them develop both concepts and practice with each other;

- and ‘learning through production’, where they reflect on and represent what they have learned to communicate it to the teacher.

Figure 2.2 – The 6 learner types in the conversational framework (based on Laurillard 2012: 90).

Peer assessment touches upon all aspects of the conversational framework. However, peer assessment has a distinct double-focus on the peer modeling cycle and the peer communication cycle. Peer assessment is a form of “asynchronous collaboration” through which students train specific communicative skills in different roles that will help them to grow collectively.

The feedback from peers can be “confirmatory, suggestive, or corrective” and it “can reduce errors and have positive effects on learning” (Topping 2009: 22). Its learning design lets students give constructive feedback and receive (and acknowledge) their peer’s feedback. And if the assignments and the implementation is thoughtfully designed, the gains can spill out to improvements in thinking skills and self-awareness, writing and communication skills, and in saving instructor’s time spent on grading. Based on several studies, one could summarize that if done right, the reliability and validity of peer assessment is as high and sometimes even higher than instructor-based assessments (Topping 2009: 24, 26).

When linked to developing critical thinking skills, peer assessment can train students in practicing epistemic vigilance in reasoning. As a form of asynchronous collaboration, peer assessment focuses on several ways of learning, primarily learning through discussion, learning through collaboration, and learning through production (Laurillard).

The didactics allows (to a certain degree) that instructors can remain in a coaching role and do not become judges, while students are elevated (and made responsible and held accountable) to co-teach through giving constructive feedback.